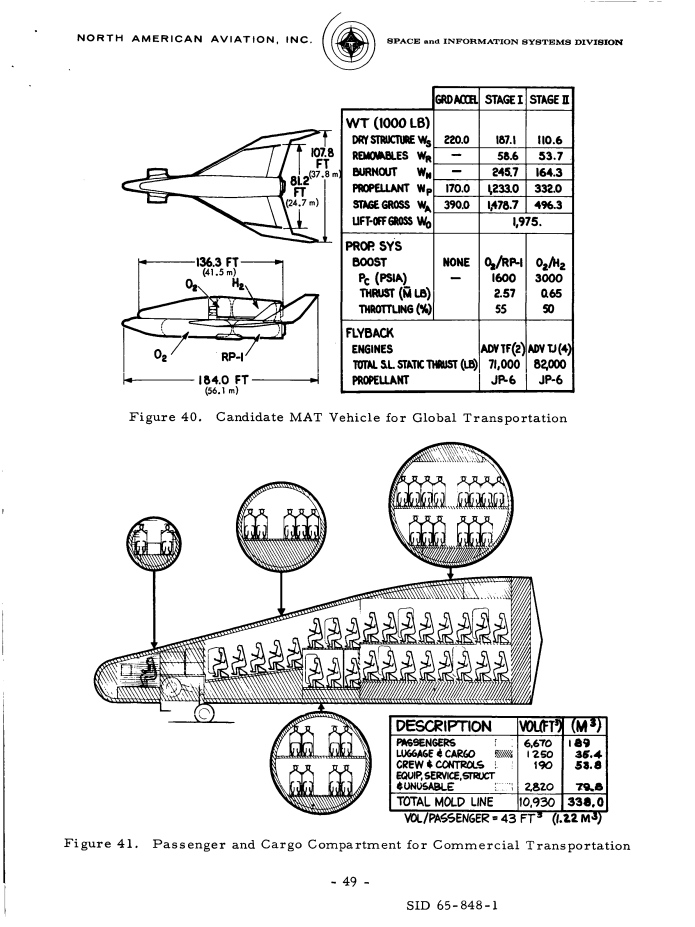

In 1965 North American Aviation produced a study for NASA about reusable space launch vehicles to support forthcoming expected space stations. Included within that study was an alternate use of rocket vehicles… point-to-point hypersonic commercial passenger transportation. This concept goes back to the late 1940’s and has continued to the present day, with the Elon Musk suggesting that the SpaceX Starship could be used for that purpose. The idea is interesting and it certainly *could* work. But could it be commercially cost effective? History with craft such as the Concorde and the Shuttle argue strongly against an early vehicle like this doing anything but losing truckloads of cash every time it launches.

Once again Patreon seems to be becoming unstable. So I’ve got an alternate: The APR Monthly Historical Documents Program

For some years I have been operating the “Aerospace Projects Review Patreon” which provides monthly rewards in the form of high resolution scans of vintage aerospace diagrams, art and documents. This has worked pretty well, but it seems that perhaps some people might prefer to sign on more directly. Fortunately, PayPal provides the option not only for one-time purchases but also monthly subscriptions. By subscribing using the drop-down menu below, you will receive the same benefits as APR Patrons, but without going through Patreon itself.

Given the craziness going on, I decided that what the world clearly needs is something consistent. Like, say, me posting one piece of aerospace diagram or art every day for a month or so. So I’m going to do that. But in order to keep people from getting too complacent, I’m posting some of them on this blog, some on the other blog. Why? Because why not, that’s why. I’m slapping the posts together now and scheduling them to show up one at a time, one a day. Given the pandemic… who knows, this little project might well outlive *me.*

So, check back in (on this blog or the other) on a daily basis. Might be something interesting.

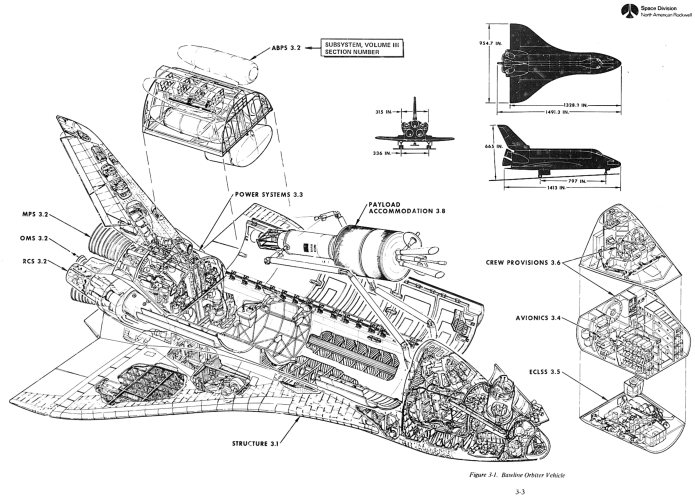

The North American Rockwell proposal for the Space Shuttle Orbiter. It is clearly *close* to what actually got built, but there are important differences. The airlock is in the nose and the OMS pods are lower on the sides of the rear fuselage and the rear portion of the cargo bay could be fitted with a pod that includes flip-out turbofan engines for range extension and landing assistance.

The full-rez scan of this diagram has been made available to all $4 and up APR Patreons and Monthly Historical Document Program subscribers. It has been uploaded to the 2020-02 APR Extras folder on Dropbox for Patreons and subscribers. If interested in this piece or if you are interested in helping to fund the preservation of this sort of thing, please consider becoming a patron, either through the APR Patreon or the Monthly Historical Document Program.

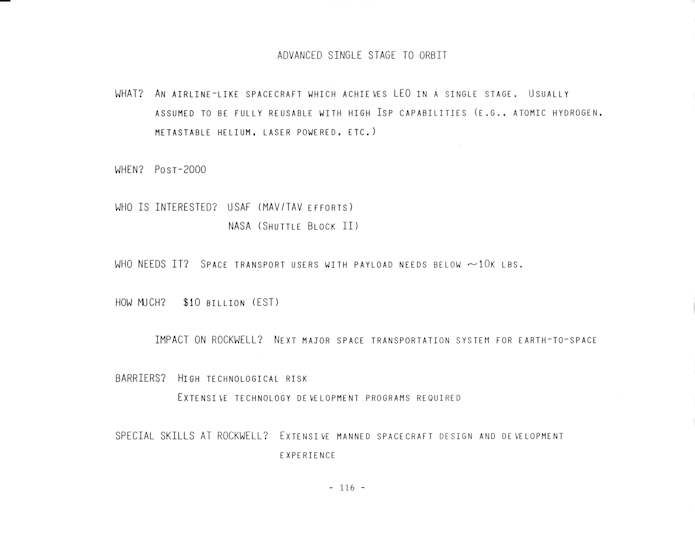

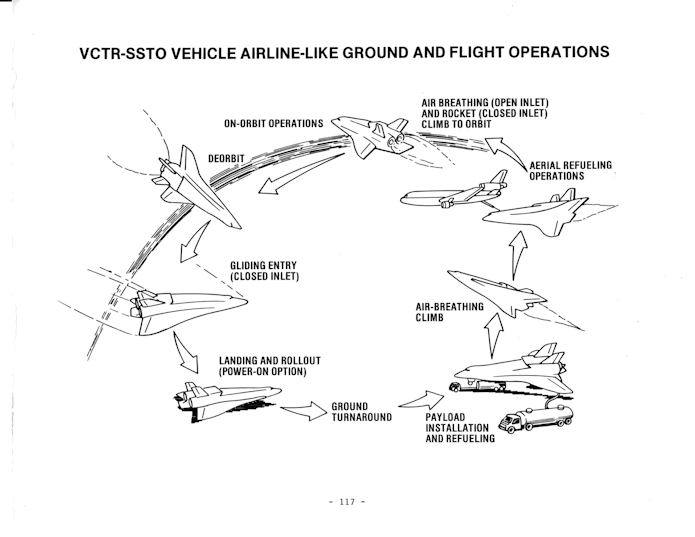

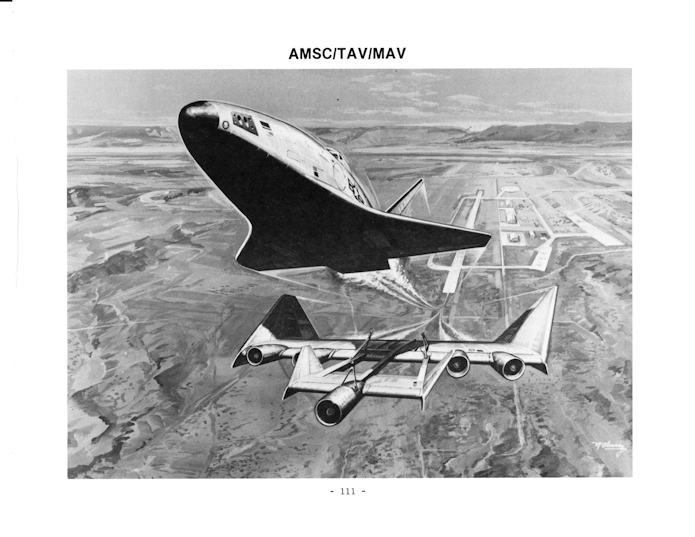

In 1985, Rockwell International considered the business case of an advanced single stage to orbit vehicle. The design illustrated was a manned, winged horizontal launched, horizontal landing design with, oddly, air inlets on the upper surface. Unlike the “Orient Express” or NASP designs of the time, this design was not meant to lift off and accelerate to Ludicrous Speed using scramjets, but was to lift off and rather sedately rendezvous with a tanker aircraft. This… is a bit familiar.

In the late 1990’s I worked for Pioneer Rocketplane. Our plan was to design and build a spaceplane that would lift off from a runway under turbojet power, with fuel tanks full of RP-1 and oxidizer tanks full of very little. The vehicle would rendezvous with a tanker aircraft which would transfer not jet fuel, but liquid oxygen. This is because for best performance an RP-1/LOX rocket system needs a far greater mass of LOX than RP-1. So leaving the LOX tank basically empty (a small amount was carried to keep the tank pressurized and chilled) would allow the vehicle to lift off at lowest practical mass. This lowered the mass needed for the landing gear, and lowered the surface area needed for the wings, which of course lowered the mass of the wings. The rocketplane would tank up, separate from the tanker and fire its rocket engine. In the case of the Pioneer Rocketplane “Pathfinder,” the spaceplane would reach orbital altitude, but not orbital velocity. An upper stage would boot the payload into orbit; the spaceplane would return home, either gliding or under jet power. The Rockwell design illustrated below *seems* to have been meant to operate in a similar fashion, but with the spaceplane intended to put itself directly into orbit. Most likely it would have been LH2/LOX powered, probably with SSME derivative engines.

The description in the text, though, describes very different vehicles, using propulsion system best described as highly steeped in the hypothetical. Atomic hydrogen and metastable helium are great stuff if you can get them… and, basically, you can’t. Not with 1980’s tech, not with 2020 tech. Someday, maybe.

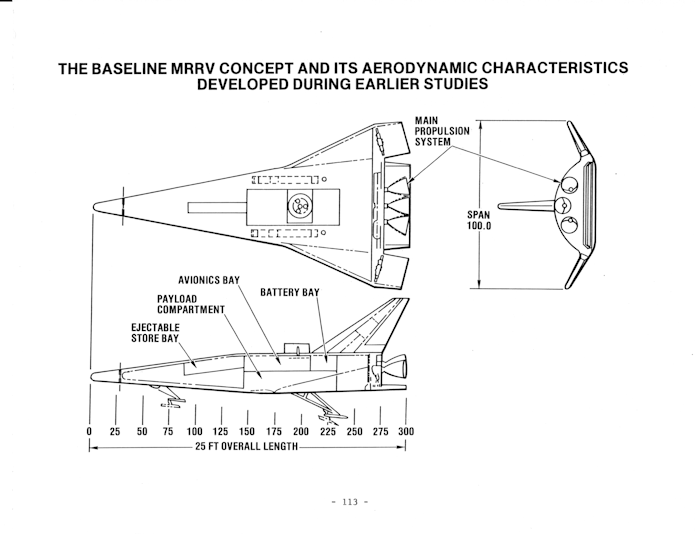

In 1985 Rockwell thought that there might be a business case for a small unmanned spaceplane for recon purposes. At the time, the answer was apparently no… but within a few years Rockwell developed the “REFLY” spaceplane which, over a span of a couple decades, transmorgified into the X-37B which has flown a handful of top secret long duration missions.

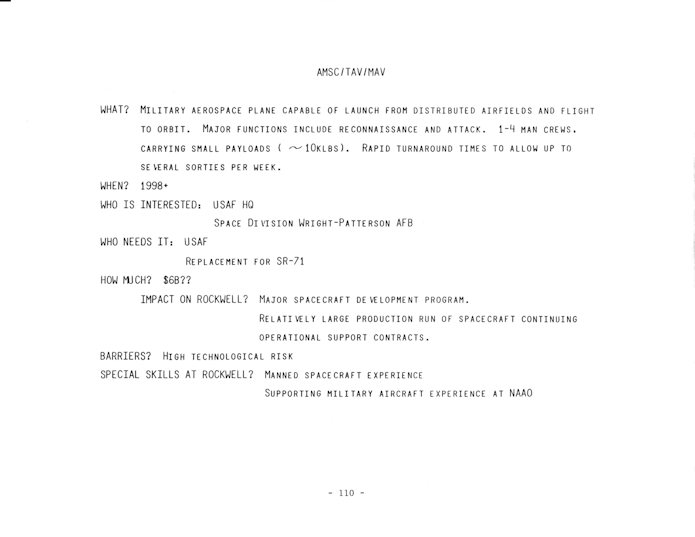

In the 1980’s, military spaceplanes were all the rage… at least on paper. In 1985 Rockwell International considered the possibility that there would be a profitable business case for a relatively small manned spaceplane that could serve as a rapid-reaction launch system for missions such as recon. Thirty years later the X-37 finally accomplished something sorta along those lines, though without the crew and rapid reaction.

Here’s an article from “Future Life” magazine, May 1979, describing a Rockwell concept for a passenger module for the Shuttle. This could carry 74 passengers, a loadout that seems perhaps excessive until you realize that it was meant to transport the crews who would build the miles-long solar power satellites. If this concept is of interest, be sure to check out US Bomber Projects #06, the Solar Power Satellite Launch Special. There, another concept for a Shuttle “bus” was described and illustrated.

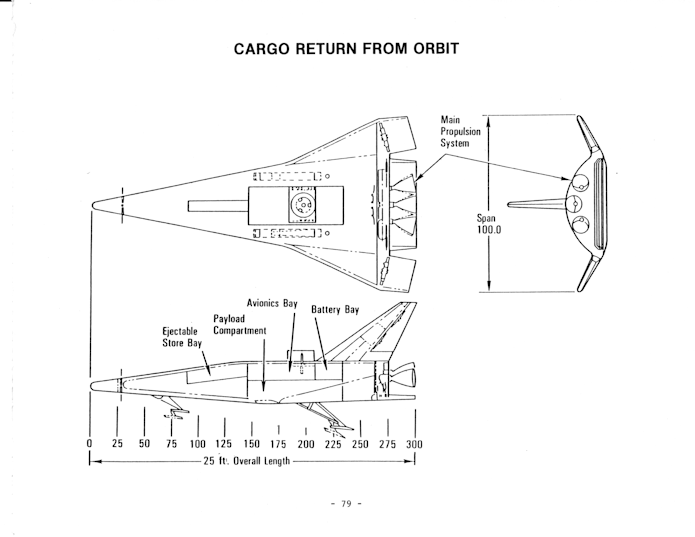

In 1985, Rockwell considered the possibility of making a business of returning commercial cargoes from orbit. This is a tricky proposition: almost *nothing* in space is worth more returned back to the ground. Humans, of course, and highly hypothetical products made in zero-g… drugs, crystals, electronics. but none of those actually panned out: zero-g and/or high vacuum might produce some small benefit for various chemical processes, but terrestrial manufacture is so much easier and cheaper that nothing has so far come from on-orbit production

The description mentions a “ballistic cargo carrier,” but the piece is illustrated with a lifting body. This appears to be the same vehicle mentioned previously as a “hypervelocity research vehicle.” I don’t know if this means Rockwell gave thought to using the HRV as a cargo return system (if so, it would be an inefficient way to go) or if the HRV diagram was simply conveniently at hand. A ballistic capsule would probably be by far the best way to go for returning payloads that are relatively insensitive to g-forces. Cheaper, smaller, lighter and, importantly, cheaper than a lifting body.

Next up: Space Station Lifeboats.