Protected: APR July rewards catalogs

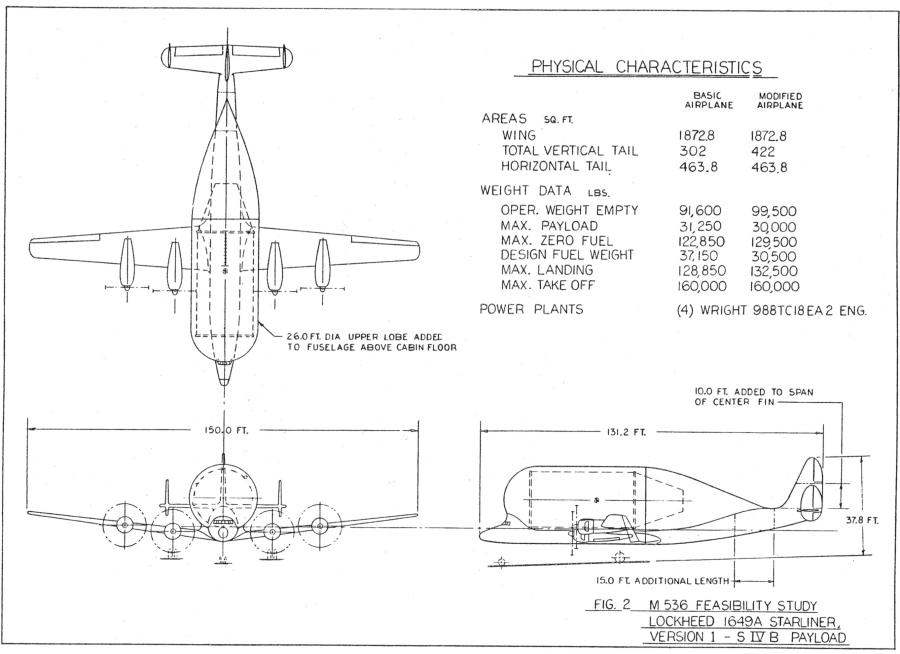

In 1964 Fairchild Stratos pitched a number of concepts for converting aircraft into carriers for Saturn rocket stages. One idea was a highly modified Convair B-36; this concept was illustrated in US Transport Projects #4, available HERE. Another was to convert a Lockheed Starliner, the final form of the venerable Constellation line of passenger airliner. This was not as massively modified as the B-36. Here, the Fairchild M-536 had a large aerodynamic “pod” was added to the top that would fit a S-IV stage. The fuselage was lengthened by 15 feet and the central vertical stabilizer was extended.

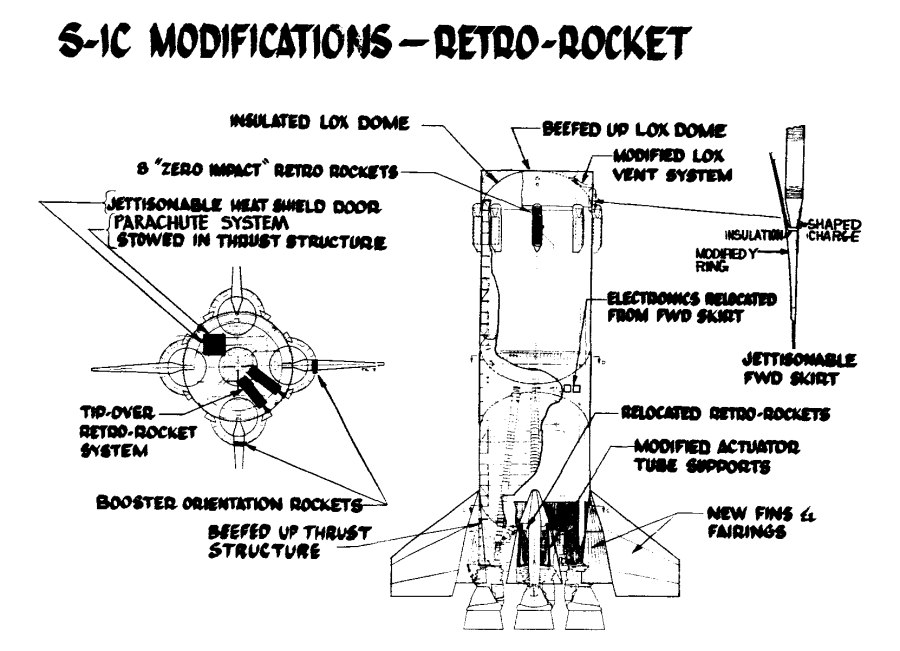

An illustration from a 1964 Boeing report on Saturn V first stage recovery and re-use. A number of concepts were studied, from balloons to parachutes. This particular one used parachutes to slow the stage and solid propellant retro-rockets in the nose for terminal braking, doing something akin to Falcon’s “hoverslam” just before splashdown. The forward LOX dome in the concept would be structurally strengthened to survive the impact. After the initial splash, rockets would be used to tip the stage over in a particular direction… and then more, bigger rockets would be used just before the stage fell over to keep it from hitting too hard.

Another concept was to use a design that would blow off the LOX tank forward dome before impact. The stage would thus hit the water like an inverted cup. As the water compressed the air within the LOX tank, blowout doors at the “bottom” of the tank would, well, blow out, giving the compressed air somewhere to go. This would serve as a pneumatic shock absorber for the stage, but it would pretty much trash the LOX tank.

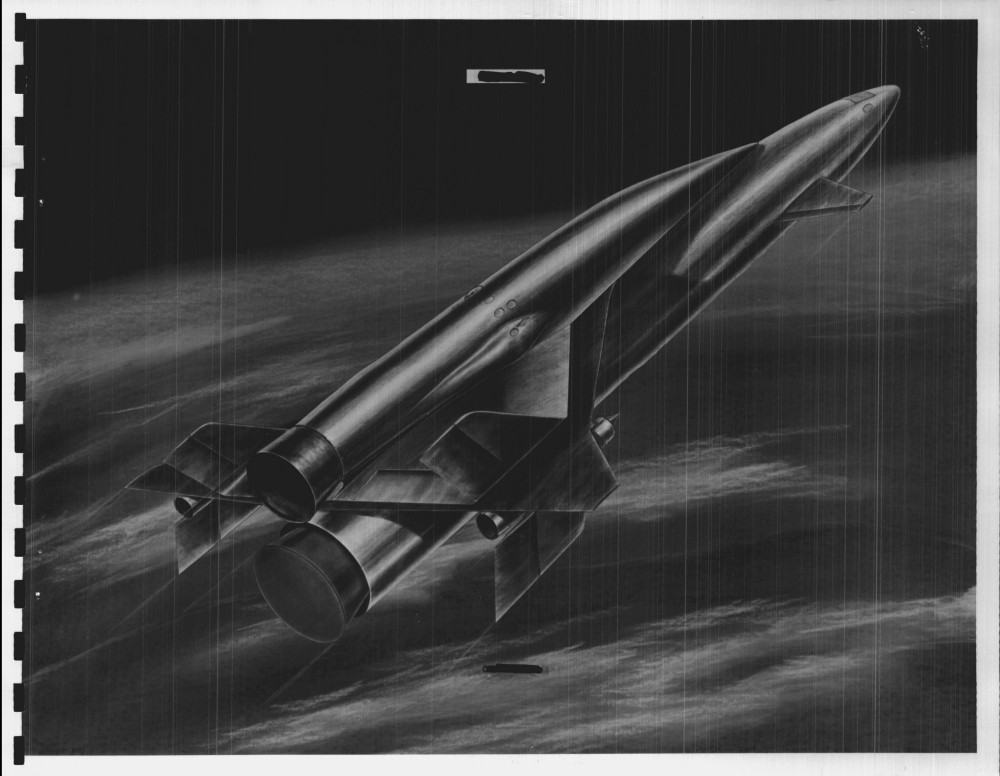

In 1963-64, NASA was looking forward to a very bright future. Moon landings within a handful of years, a serious space station or two in the early seventies, manned missions to the vicinity of Mars and/or Venus probably by the early eighties, manned Mars landings not long after. Moon bases, Mars based, nuclear rockets, missions to the asteroids and the moons of Jupiter… in 1964, the rest of the 20th century must’ve looked *fantastic.*

In order to pull all that off, it was clear that NASA would need to launch a *lot* of astronauts. Consequently, a request for proposals went out to the aerospace industry to design the capability to do just that. Boeing, North American, Martin, Lockheed… a great deal of interest was shown and work accomplished. One design produced is illustrated below, a Lockheed design for a two-stage fully reusable spaceplane capable of transporting ten tons of payload or ten passengers to an orbiting space station. The booster stage had a cockpit about where you’d expect; the spaceplane, conversely, had an offset spaceplane so that the crew would have *some* sort of forward view during landing. Both stages used advanced rocket engines; the first stage also had turbojets to get it back to the launch site. As with all pre-Shuttle designs, estimates of turnaround time and minimal launch cost are impressive and a bit depressing in just how fabulously optimistic they were.

An earlier three-stage concept was shown in US Launcher Projects #5.

The future looked bright. And then… LBJ.

It is common practice for an aerospace company to crank out many and sundry concepts for derivatives of the aircraft they produce (if they didn’t, Aerospace Projects Review never would’ve come to be). This is certainly true for jetliners. And of course, in many cases derivative are in fact produced… the DC-9, 707 and 737, for instance, saw many stretched, stretched further and stretched some more designs enter service, packing more passengers onto airframes that don’t cost much more to buy or operate.

One derivative that went no further than the concept stage was a 1970’s Lockheed idea for a twin-engine version of their three-engined L-1011. This would have been a *smaller* aircraft, but presumably cheaper, more economical to operate as an “airbus” on shorter routes. However, there were already a number of jetliners to fill that role, and with as expensive as the L-1011 turned out to be to maintain and keep flying, this idea basically never had a chance.

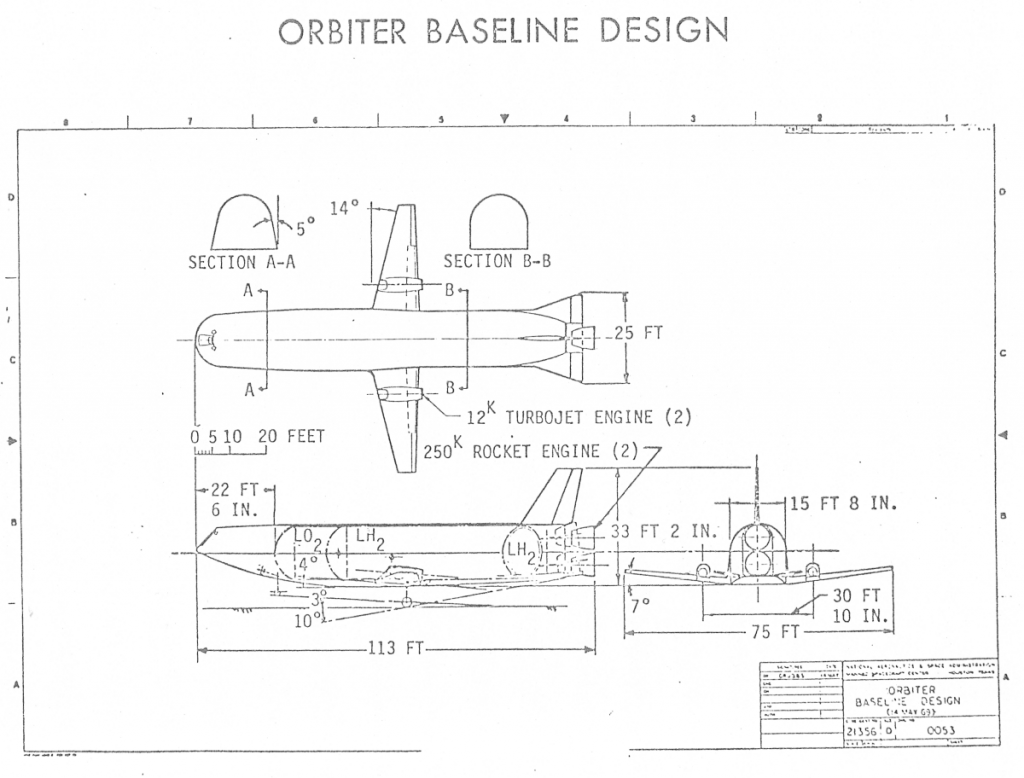

The orbiter for the “DC-3” referenced previously. This vehicle had relatively small wings, leading to quite low crossrange. The wings were also simple straight wings, not highly swept deltas; the vehicle could get away with this because it did not “glide” during re-entry, but “belly flopped.” To aid in crossrange and landing, each wing would have a single turbofan in a sealed pod. The payload bay is not shown here, but would be quite small and right behind the cockpit.