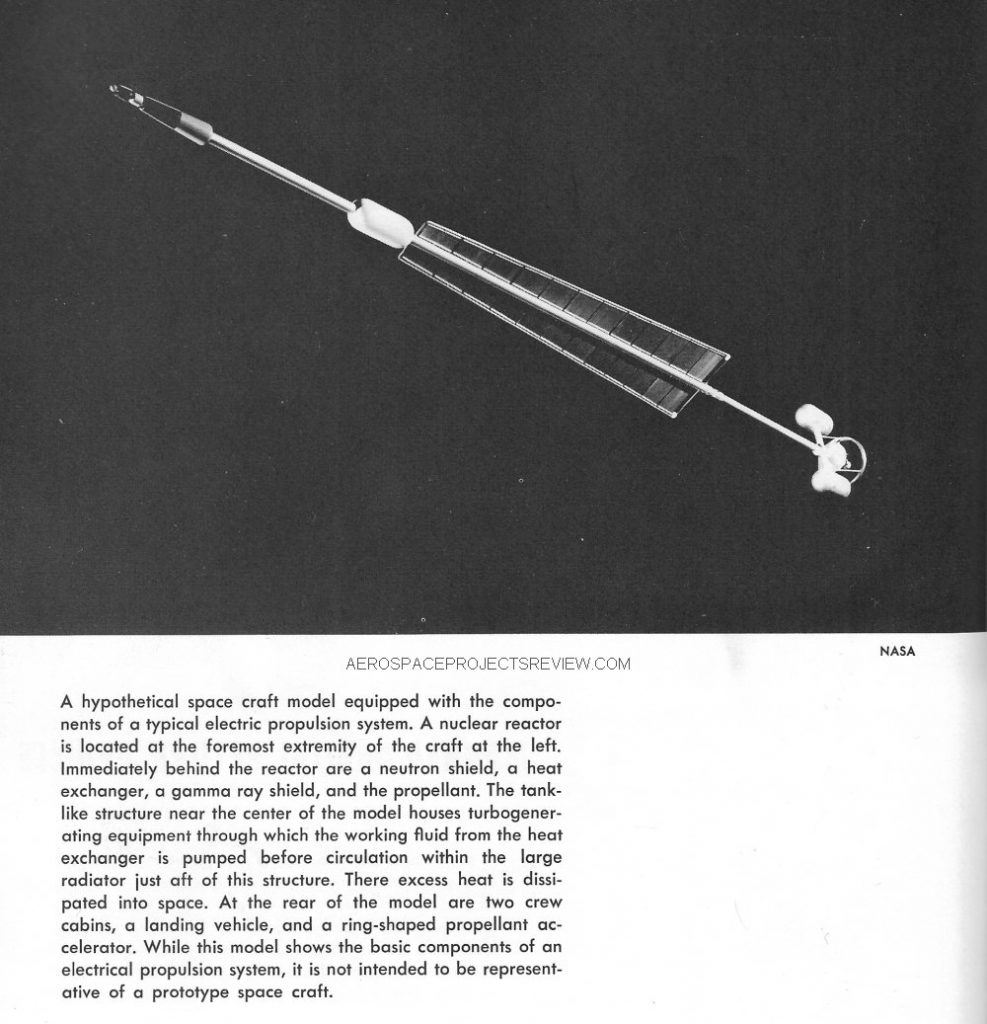

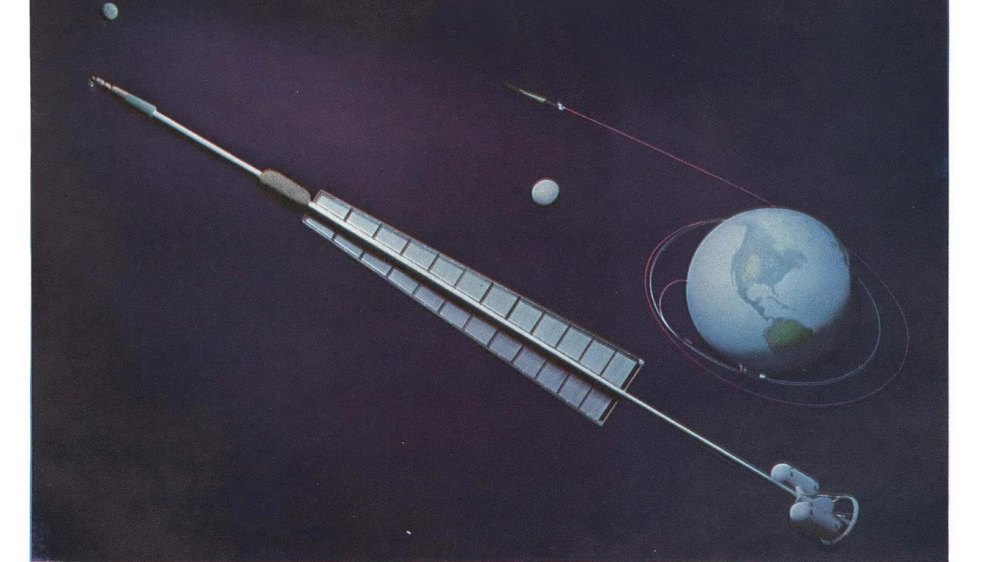

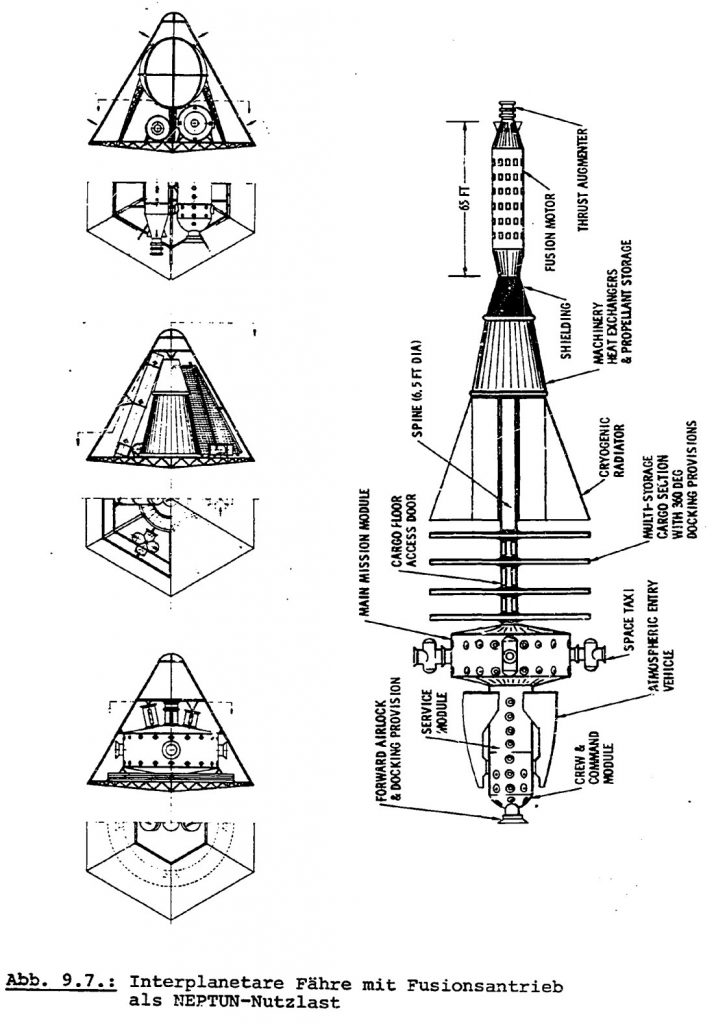

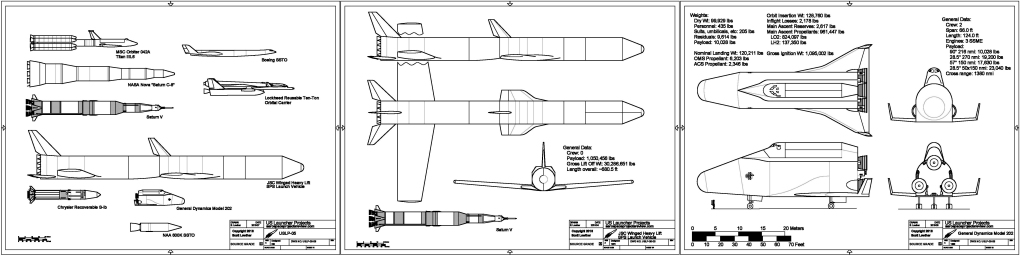

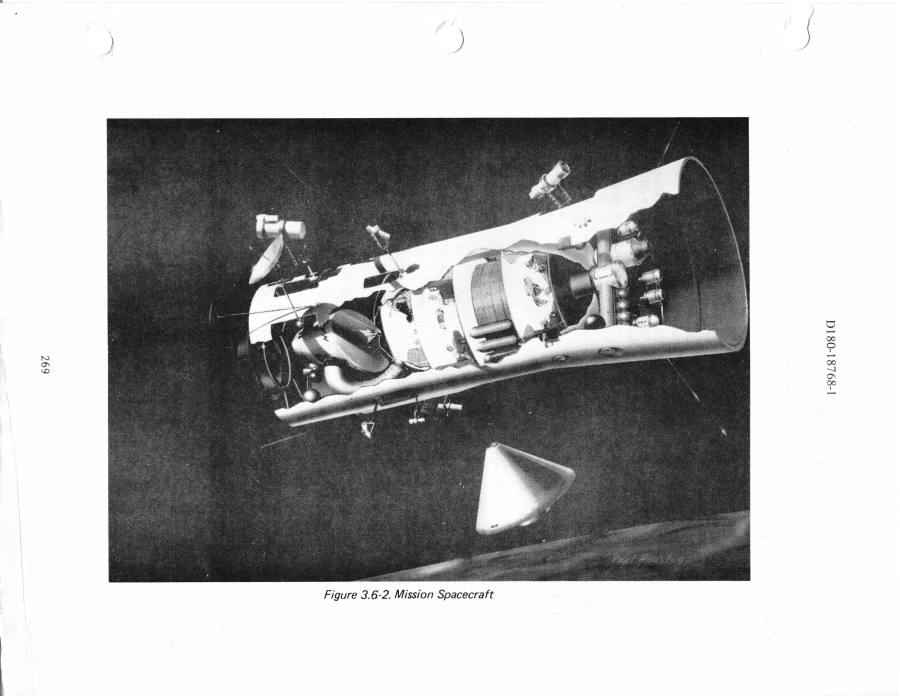

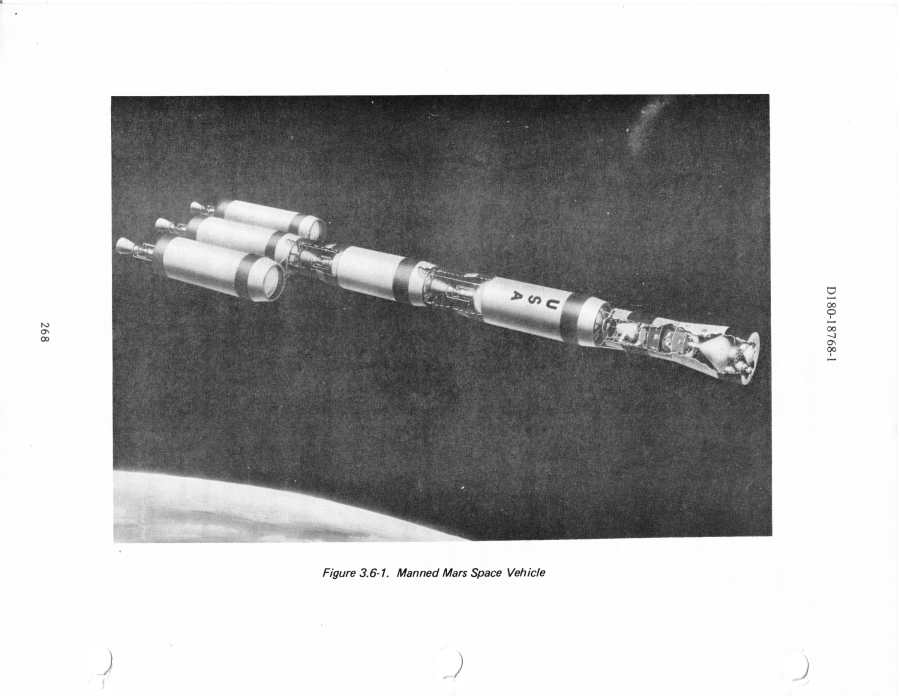

A NASA model circa 1959 illustrating the general configuration of a nuclear-electric spacecraft for the exploration of Mars. While apparently not meant to represent a serious design proposal, the general configuration is much the same as those created decades later. It features a nuclear reactor at the nose, a long boom with a pair of radiators to get rid of the heat produced by the reactor, and payload at the tail. Payload includes crew areas and an indistinct lander. The ring at the rear is the “propellant accelerator,” which is not described; presumably it is a structural ring holding a bank of ion engines or the like.

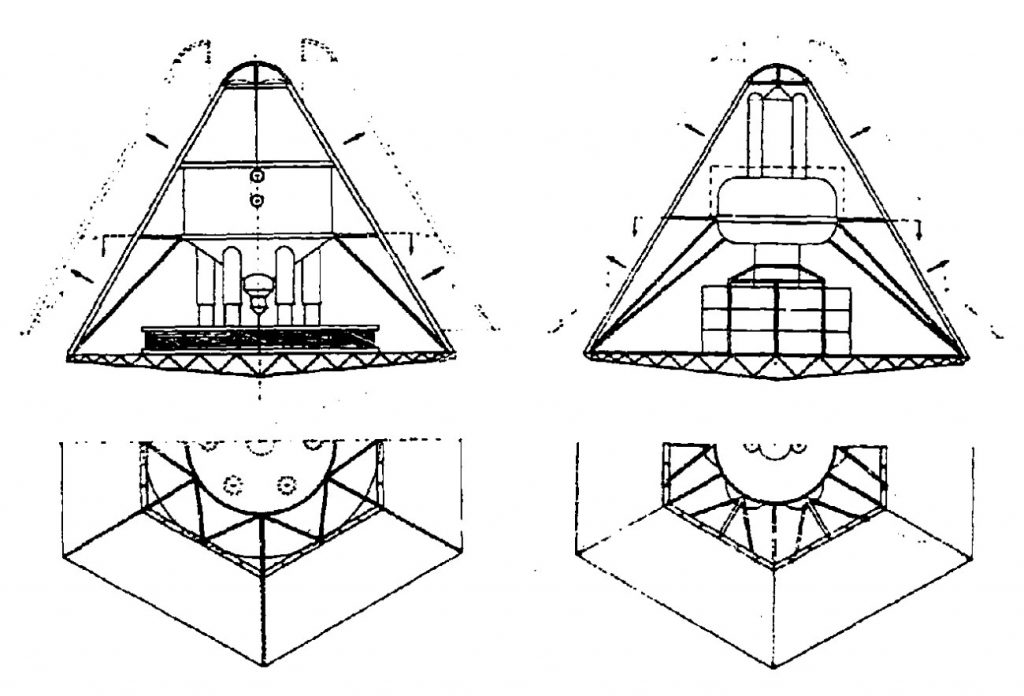

Note that the radiators are tapered. This is common in such designs: the gamma ray and neutron shields behind the reactor only block a relatively small portion of the emitted radiation. The radiators fit within that shadowed cone; if the radiators projected out into the unshielded volume, not only could the radiation do some damage to the structural materials it would also heat them up… defeating the whole point of radiators.

This basic layout would still be applicable today, with the main difference being that the engines might well be located elsewhere, firing in a different direction. The reactor could well be at the tail; leaving the engines where they are would turn the long boom into a structure in tension, meaning that the reactor would be “hanging” down. This would be structurally more efficient… after all, the reactor could certainly hang from a string, but a ship could hardly push on a string. Or the engines could be located near the ships center of gravity, firing “sideways.” This would be trickier for the boom, but if the engines are indeed low-thrust ion engines, the forces involved would be almost negligible. Or with a similar arrangement the ship could be made to tumble end over end; with the engines at the CG they could continue to fire “sideways” while the crew enjoyed at least some measure of artificial gravity.