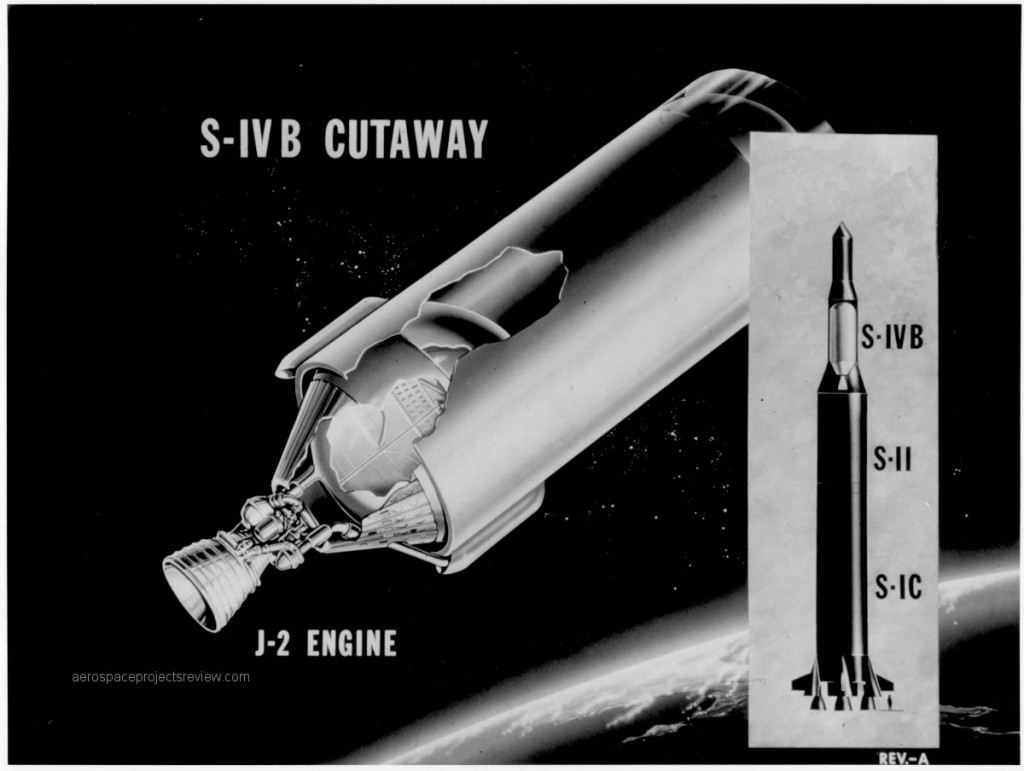

NASA art depicting the third stage of the Saturn V. A bit different from what actually got built. Date uncertain… probably ca. 1963.

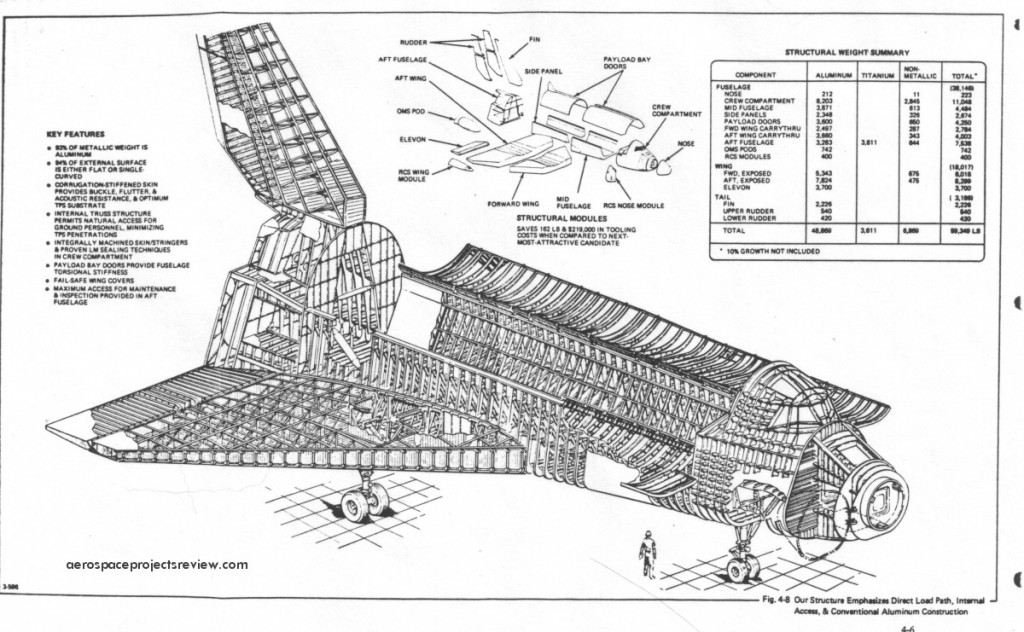

A little-known and poorly-documented proposed variant of the Titan family of launch vehicles, the Titan IIIG used an increased-diameter core with 156-inch diameter solid rocket boosters. The late-1960’s Titan IIIG would have been capable of launching 100,000 pounds, and seems to have been focused on USAF missions. McDonnell Douglas appears to have considered it for use in launching the Big Gemini logistics capsule. Beyond that, not much is known. The McD illustration below is one of the few I’ve come across, and does not seem likely to be terribly accurate. Also depicted here are the Titan IIIM, a launch vehicle composed of a cluster of four 156-inch solids topped by an S-IVb stage (a McD product), a 260-inch solid topped by an S-IVb, and external tank arrangements for reusable launch vehicles such as the ILRV (integral Launch and Recovery Vehicle), a predecessor to the Space Shuttle. McD’s entry to the ILRV study was a derivative of their generic Model 176 concept.

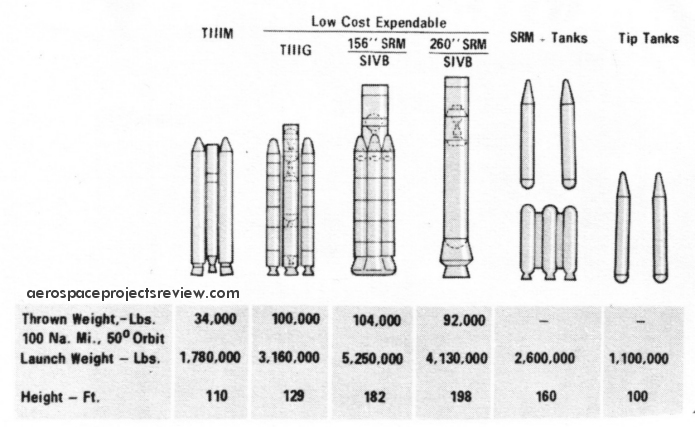

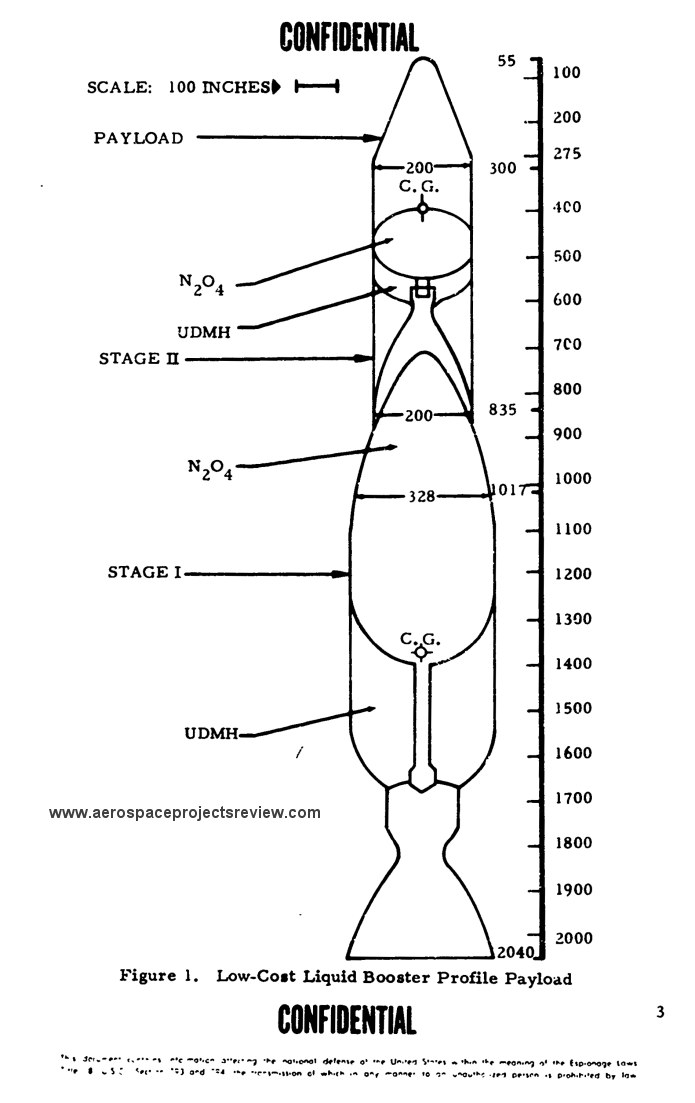

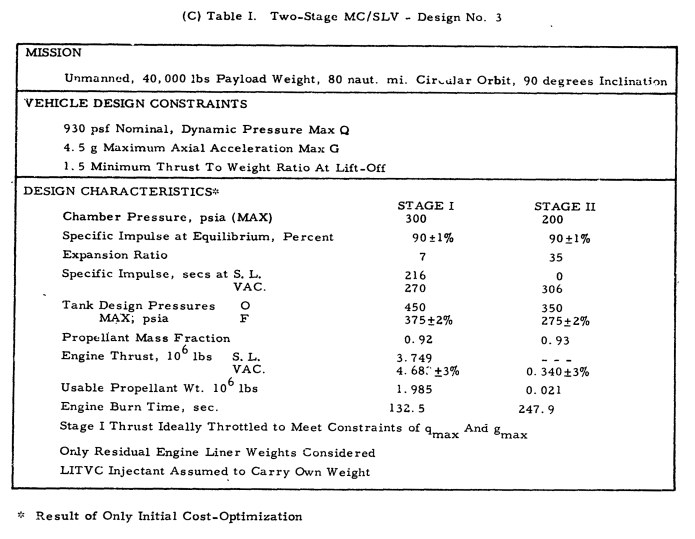

In the late 1960s, prior to the Shuttle concept really taking off, the USAF funded studies of low cost boosters. One type that received considerable study was a two-stage pressure fed layout. This was vaguely similar to the earlier Aerojet Sea Dragon in that it would be a heavy and simple design, using shiplike construction and dense propellants. The nature of the first stage booster was such that recovery was anticipated. Propellants were hydrazine and nitric acid.

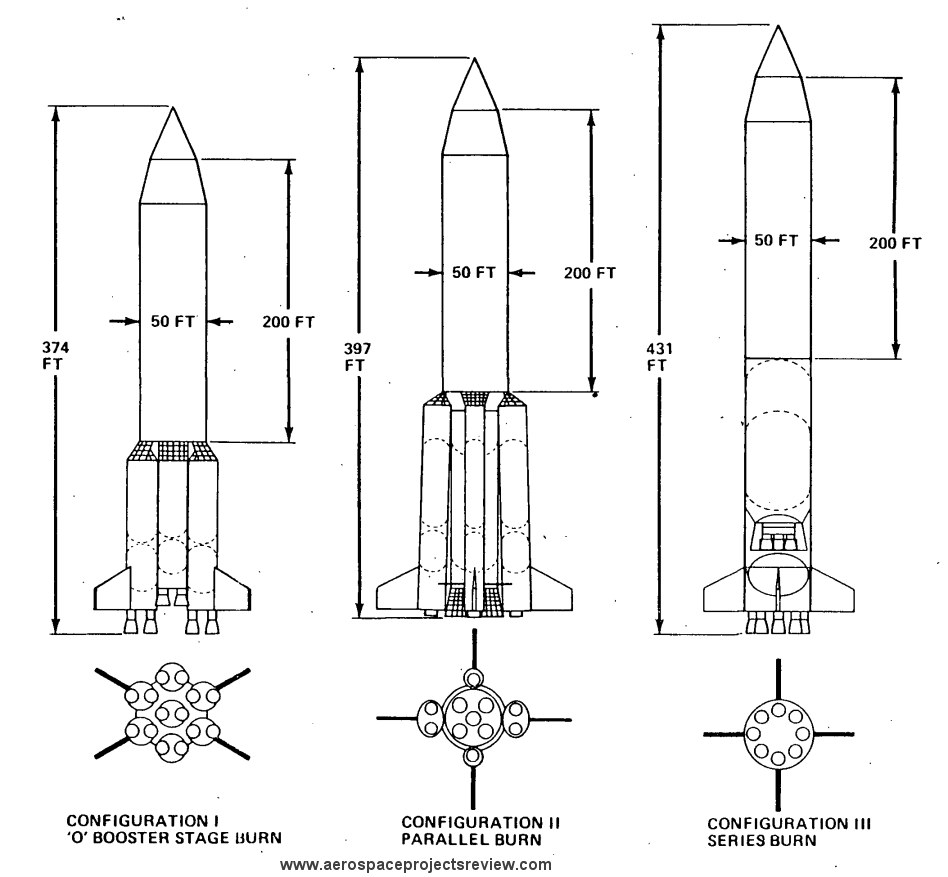

A trio of NASA-Marshall heavy lift launch vehicle concepts, circa 1985. The first two configurations used a clustered booster stage; the third configuration used series staging, with a unique feature than the booster stage had no LOX tank, only a kerosene tank. The LOX for the first stage was contained within the second stage. This would make the vehicle more complex, but it would also make the first stage more recoverable.

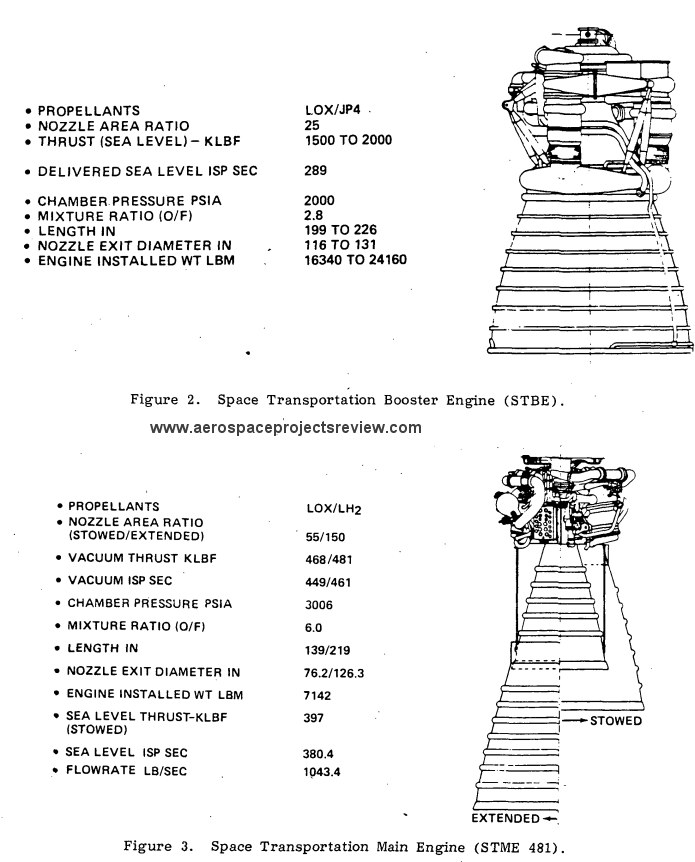

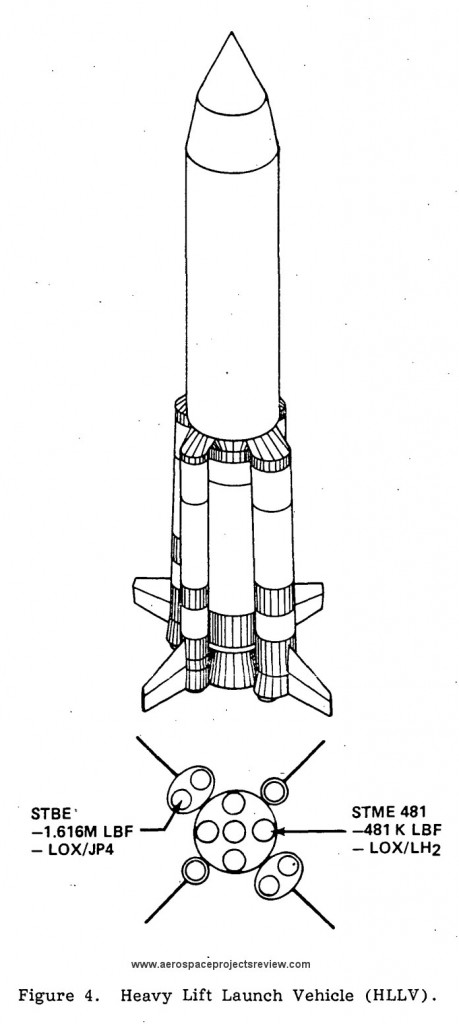

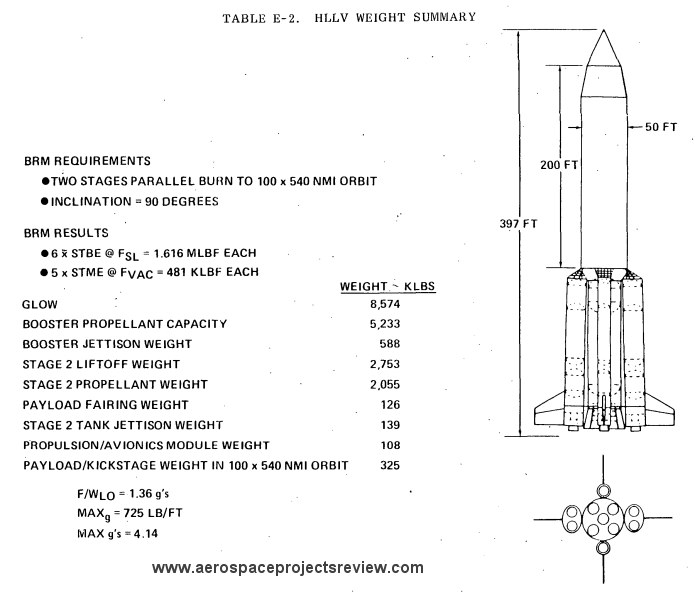

The three designs were designed for the same mission, launching 300,000 pounds to LEO (specifically a 100X540 nautical mile transfer orbit, with circularization at 540 n. mi. to be performed by a kick stage). All three used an all-new LOX/kerosene booster engine, the Space Transportation Booster Engine, slightly more powerful than the F-1. All three used a new LOX/LH2 upper stage engine, the Space Transportation Main Engine, on the core vehicle. The STME used an extendable nozzle for good performance at both low and high altitude.

The selected configuration was #2:

The boosters for Configuration 2 were independently recoverable. The five STMEs for the core stage were contained in a recoverable propulsion & avionics module, which would splash down for recovery, refurbishment and reuse.

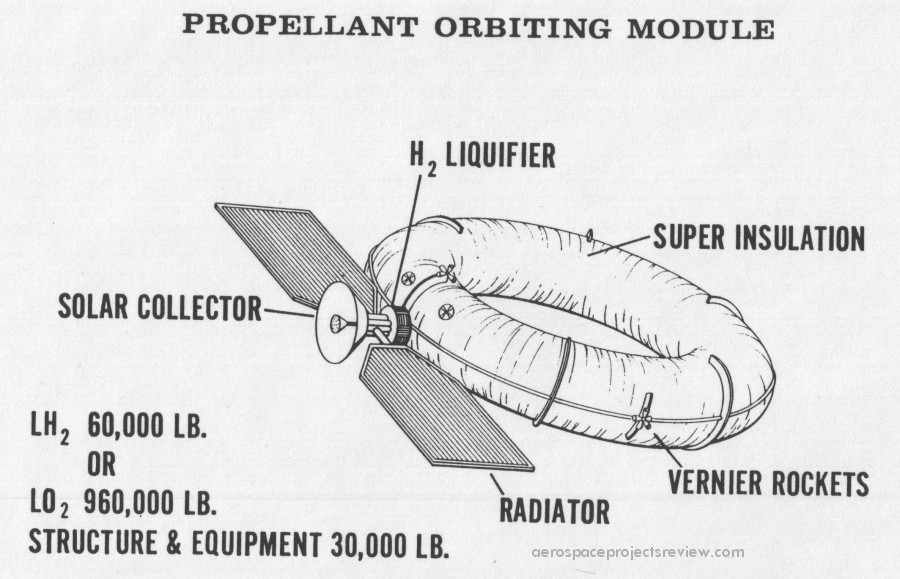

The concept of an orbital fuel depot, supplied from Earth in order to fuel missions to Mars and the like, is not especially new. Shown below is a concept from General Dyanamics from 1963, depicting a toroidal propellant depot. A torus is a rather poor shape for such a thing… not only is it heavier than an equivalent-mass spherical tank, it also has substantially more surface area. But the advantage of this configuration is that it would easily pack in excess payload space aboard a partially-loaded Nova launch vehicle. Dimensions weren’t given, but maximum diameter would be less than 70 feet.

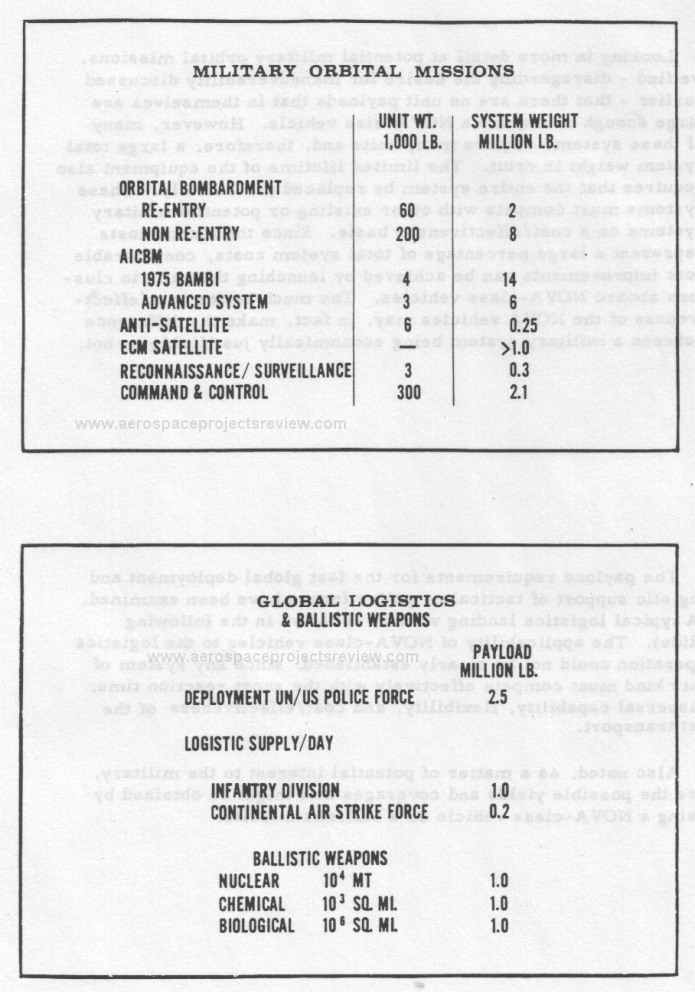

In the early 1960’s, NASA wanted the Nova rocket: a launch system capable of orbiting around one million pounds. The primary missions included manned lunar and Mars missions, space station launches, that sort of thing. But other missions were contemplated, including military missions. Information on these military missions is pretty lean. This is most likely due to the fact that Nova was a NASA project with minimal DoD input… thus there would have been minimal actual work done on military launch planning for Nova. Nevertheless, a few snippets of military Nova data have come to light from time to time.

A General Dynamics/Astronautics presentation to NASA in August 1963 had a few paragraphs and a few charts discussing military missions. Sadly there was little more; it is impossible to determine if these concepts were actually requested by NASA or not, and whether these ideas went any further. BAMBI (BAllistic Missile Boost Intercept), an anti-missile satellite system, was studied by General Dynamics at the same time as Nova, and has largely remained classified (or at least, little has been made public). Like the anti-missile satellites studied during the SDI program of the 1980’s, for BAMBI to have had a chance of success at taking out a massed Soviet ICBM strike, a large number of the satellites would be needed. In the NOVA presentation, 14 million pounds worth of satellites – each weighing 4,000 pounds – were claimed as needed. In this case, launching 3,500 or so satellites would be a chore that Nova could handle easier than much smaller launch vehicles.

More unconventionally, Nova was also proposed as a logistics transport. In this case, it could be used to chuck a capsule across the planet sub-orbitally… a capsule with 2.5 million pounds of payload. Additionally, Nova could put a 1 million pound capsule into orbit; the capsule would de-orbit itself and land to disgorge infantry. Orbital systems were in a way prefered, as orbital systems meant that the Nova itself would go into orbit. This meant that the Nova could de-orbit on command an return to Earth at convenient locations for recovery; ballistic lobs would essentially throw the Nova away. The orbital capsule was at least illustrated with a drawing.

Finally, Nova could be used to launch offensive weapons. One million pounds were the weights given, so presumably these were meant to go into orbit. The weapons loads were remarkable, and more than a little spooky:

- 10,000 megatons worth of nukes (speculation: 10,000 one-megaton warheads)

- Enough chemical weapons to kill everyone in a 1,000 square mile region

- Enough biological weaponry to kill everyone in a 1,000,000 square mile region.

Note… these weapons loads are for a single launch.

Not provide in the presentation – or anywhere else that I’ve seen – is NASAs reaction to the idea of using their rocket to launch a million square miles worth of biological horr or.

or.