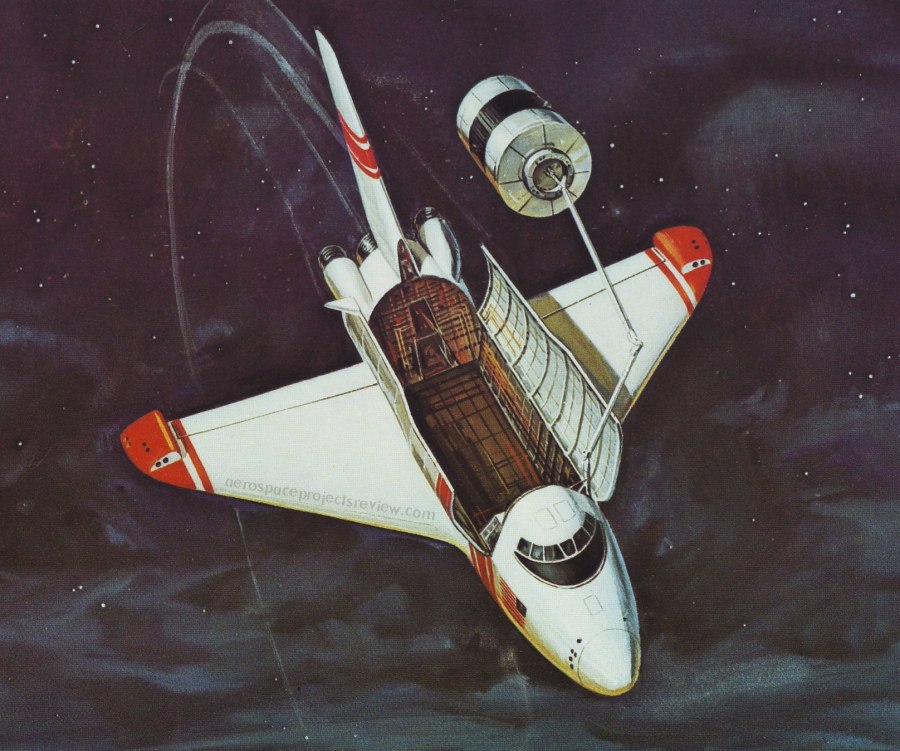

The Grumman 619 in orbit, deploying a satellite. Here you can see the humped cargo bay doors. Not visible here are turbojets in the cargo bay; they were left out of this particular mission. The orbiter would thus have to land as a pure glider.

An illustration of Grumman’s 619 Space Shuttle – the final competitor for the competition that North American Rockwell won – lifting off. This design from 1972 was laid out pretty much as the final Space Transportation System was, but with some notable differences:

1) Stabilizing fins on the external tank

2) A “humped” back

3) four turbojet engines could be stored in the rear of the cargo bay, used for landing range extension, go-around capability and self-ferrying

4) Smaller OMS pods

5) Separate reaction control pods on the wingtips

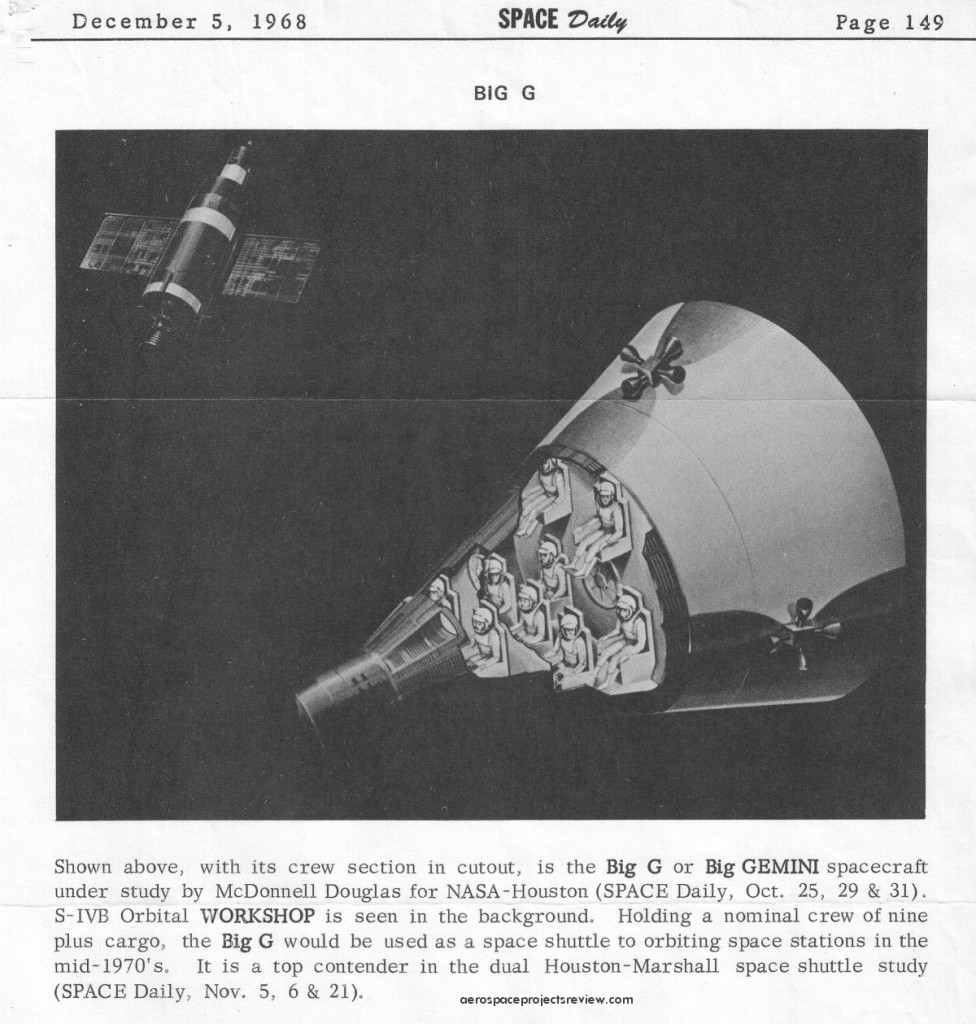

One pre-Shuttle idea for a space logistics vehicle was the “Big Gemini.” This would have used portions of the Gemini re-entry capsule as the nucleus around which a much large conical capsule would be built. The adapter section would be done away with and replaced with a conical section (with a geometry matching and extending the Gemini capsules) to house a variable number of passengers. A large number of “Big G” configurations were put forward; generally these were to be launched atop the Saturn Ib, but Saturn V and Titan IIIc options were also studied.

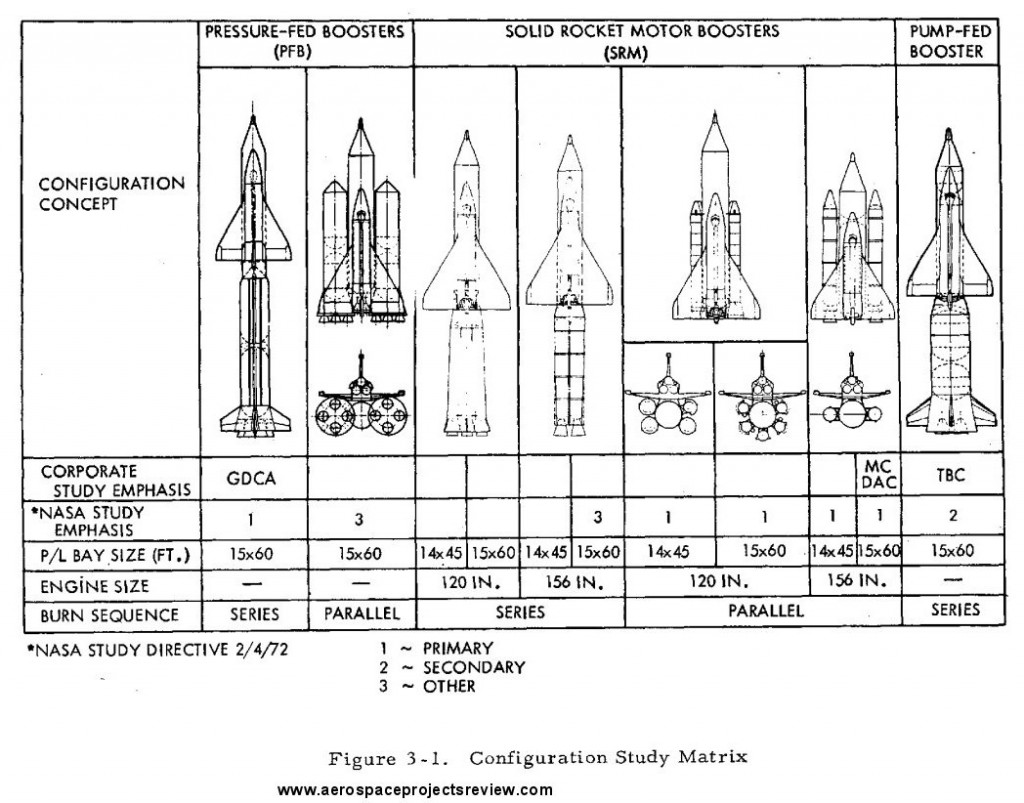

A collection of designs produced for alternate space shuttle configurations. This was the last gasp for configurations substantially different from what actually got built…. the second design from the far right became the baseline layout. But even with a recognizable orbiter and external tank, considerable variation was possible in overall launch vehicle layout. Not shown is a flyback booster option.

A Grumman alternate Space Shuttle concept with a low cross range orbiter and a trio of 156-inch diameter solid propellant rockets for the first and second stages. The orbiter itself was stuffed with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen tanks; even so, the high density of the solid rockets meant that the vehicle as a whole was remarkably compact.

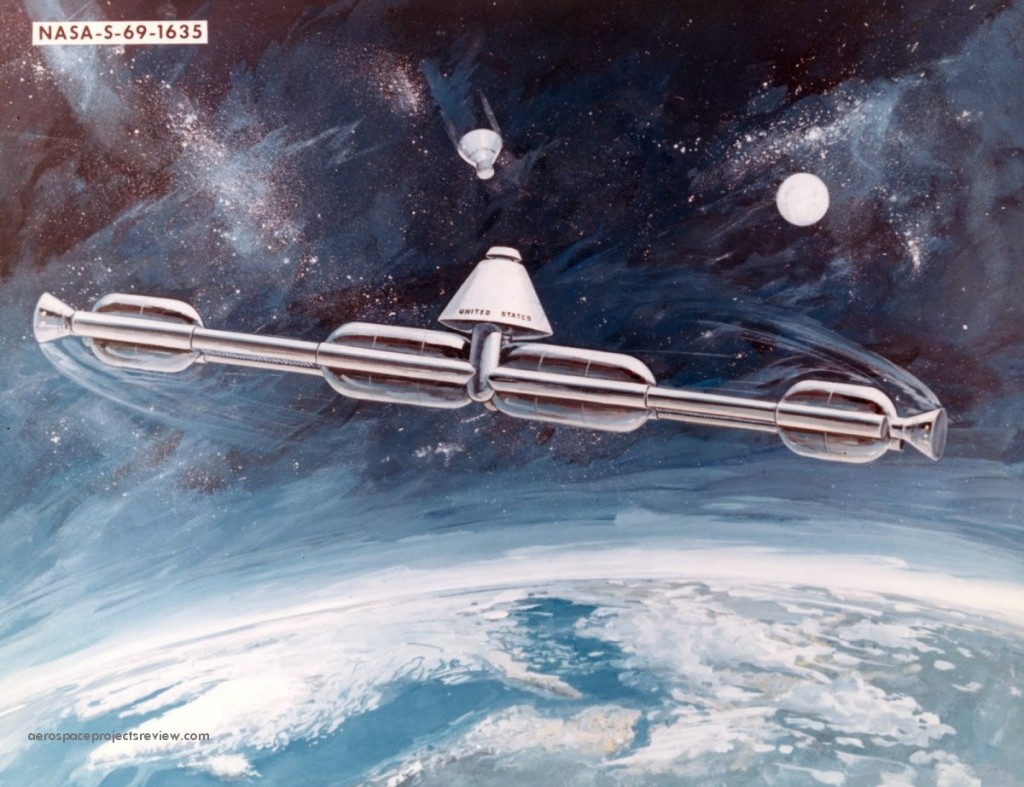

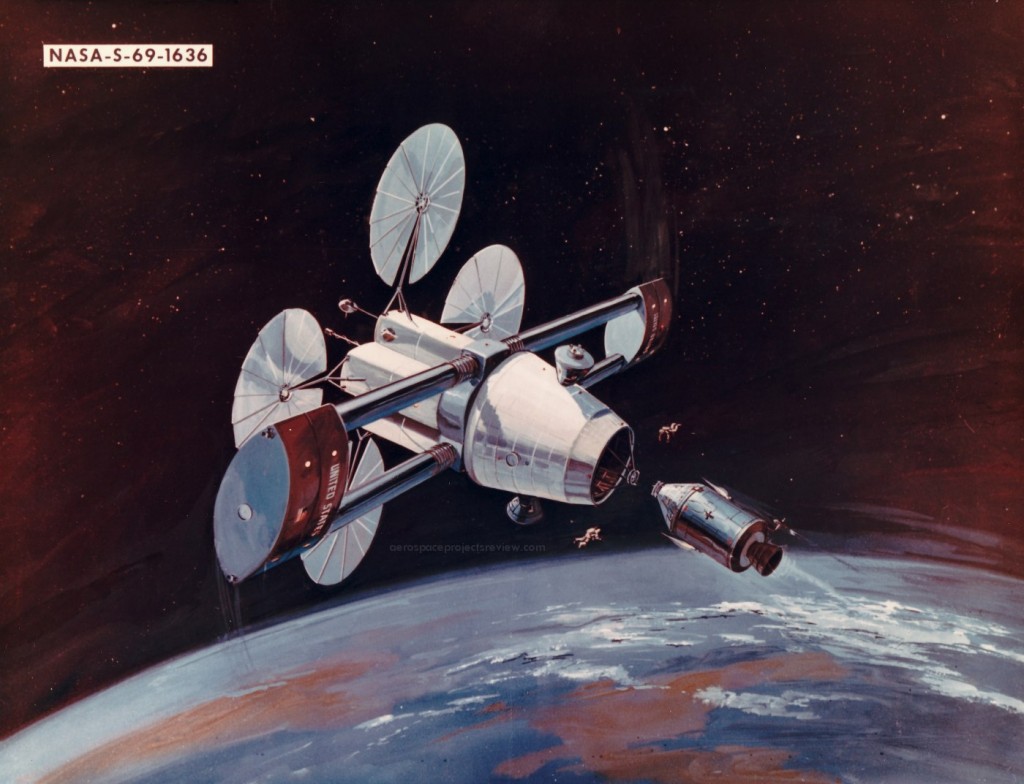

This 1969-era NASA painting depicts a space station that does not seem to make much sense. For starters: it would seem to be a single-launch station, but how would it fold up for launch? If the two arms were to fold “down,” the large pressure vessels would try to pass through each other. And it has what appear to be Apollo capsules at the ends of the arms. If this is so, it would not only mean that separating one capsule would throw the space station far off balance, it also means that an incoming capsule would be incapable of docking unless the station stopped rotating.

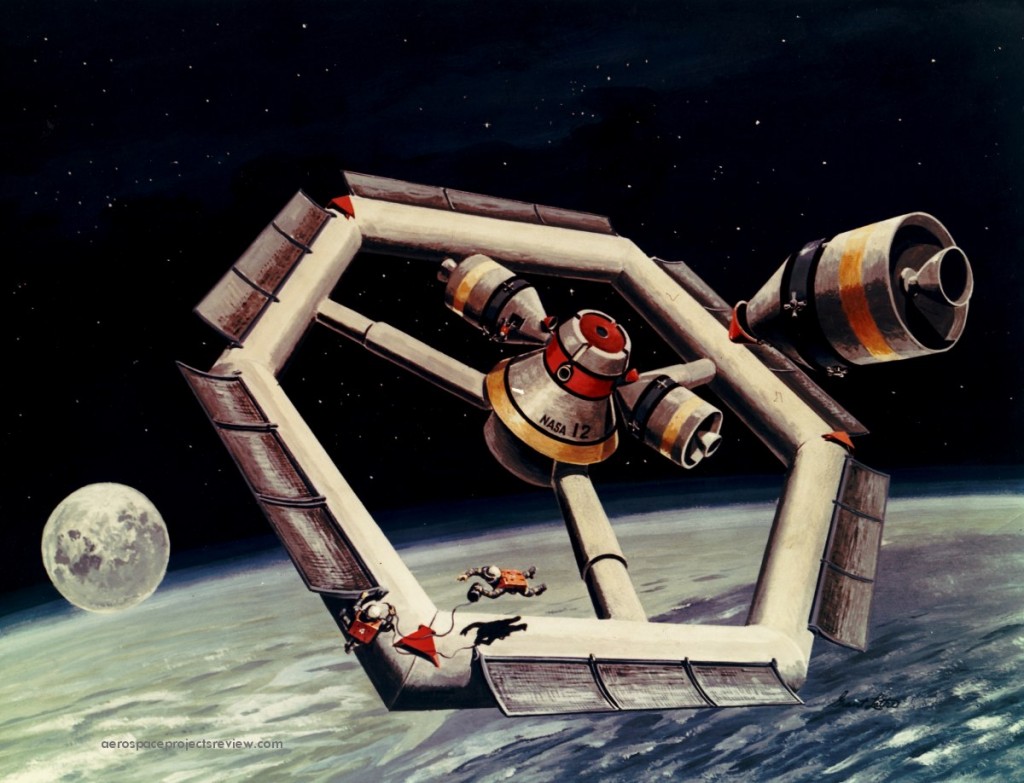

NASA artwork from 1962 depicting a single-launch space station. Launched by a Saturn V, this space station would be folded up, then would unfold once on orbit to form something of a torus. Rotation would then supply a measure of artificial gravity. With a design like this, much of the inner volume would not be very efficiently used… as the straight cylindrical segments diverge further from a circular centerline for a hypothetical truly circular torus, the more the inner surface of the segment would seem to slope “uphill.” Thus the interior would probably be stepped so that the floor would be “flat” from the acceleration vector point of view, to keep everything from rolling or sliding “downhill.” In this case the central hub appears to be rotationally decoupled.

Image is related to this radial-arm concept, and was scanned at the NASA HQ history archive.

A Grumman alternate Space Shuttle concept with a low cross range orbiter and a series of pressue-fed storable-propellant rockets for the first and second stages. Pressure-fed boosters like this are heavy and relatively low-performance, but also relatively simple and cheap. The heavy construction required for the large high-pressure tanks makes them readily recoverable and refurbishable.