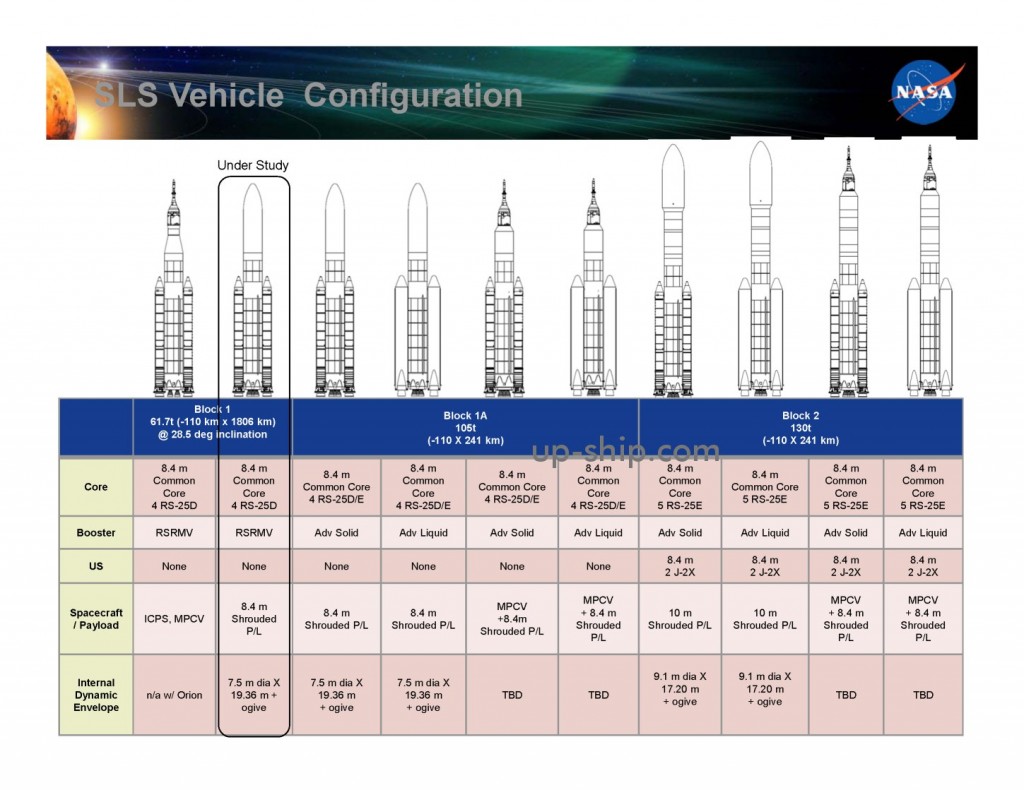

The ultimate version would strap four boosters around the core, giving the vehicle a payload to LEO of 225 tons, more than twice that of the Saturn V.

In 1993 Boeing designed a modular heavy lift launch vehicle for a range of space launch missions. The core vehicle was based on Shuttle External Tank components, with a multitude of SSME’s at the rear (in two recoverable pods). Shown here are some basic launchers built from these components, being used to launch parts for a lunar mission into Earth orbit. The Shuttle is shown with the solid rocket boosters replaced with the new core vehicles.

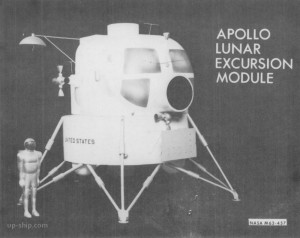

A concept for the Lunar Excursion Module, reported on in May of 1962. It seems to have originated with Maxime Faget (of Mercury capsule design fame) at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. It is interesting not only for its conical shape, but also far is basic layout… as with the Soviet LK lander, this design features a single main propulsion system that fires through a “hollow” landing stage. The Soviet design packed all the propulsion tanks into the ascent stage; this NASA design had distributed tanks. This would make the ascent vehicle lighter, at the expense of plumbing complexity. Propellants were N2O4 oxidizer and either MMH or 50% N2H4 + 50% UDMH.

This vehicle would weigh 23,959 pounds at separation from the Command Module; 11,204 at landing. At liftoff – after leaving behind the landing stage – it would weight 7,068 pounds; at burnout, 3,568 pounds.

From sometime around 1963, a few photos of wind tunnel models at NASA-Langley. Shown are a range of Dyna Soar models, from pre-Dyna Soar “HYWARDS” concepts to the initial Boeing 844 design to the final Boeing Model 2050E configuration.

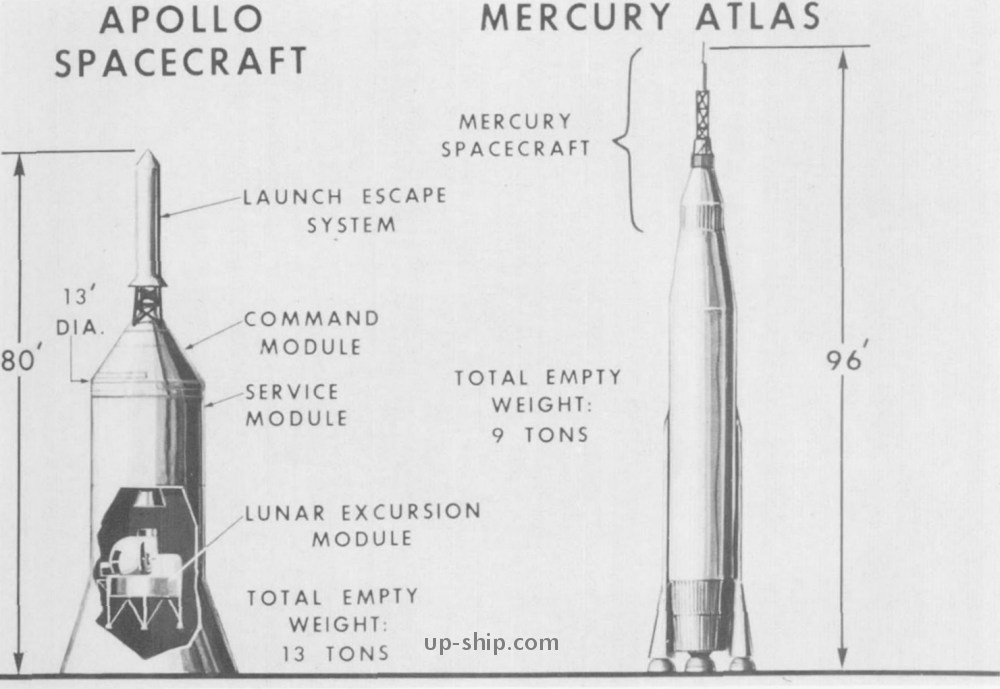

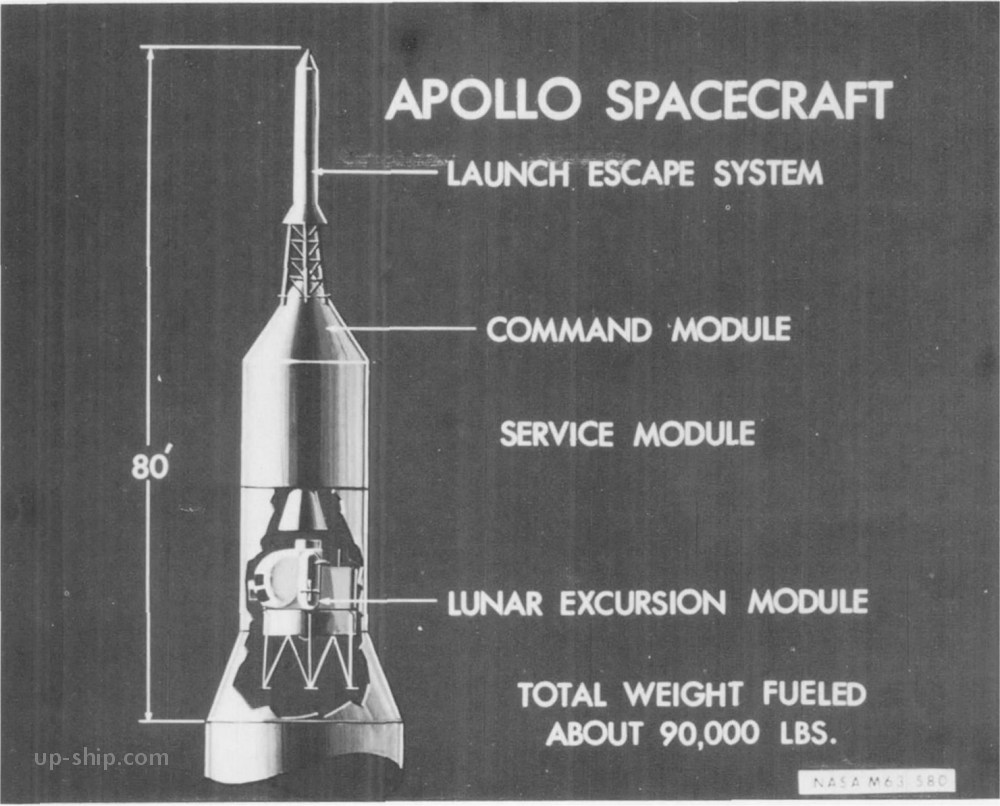

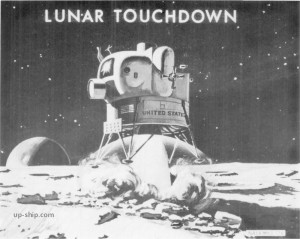

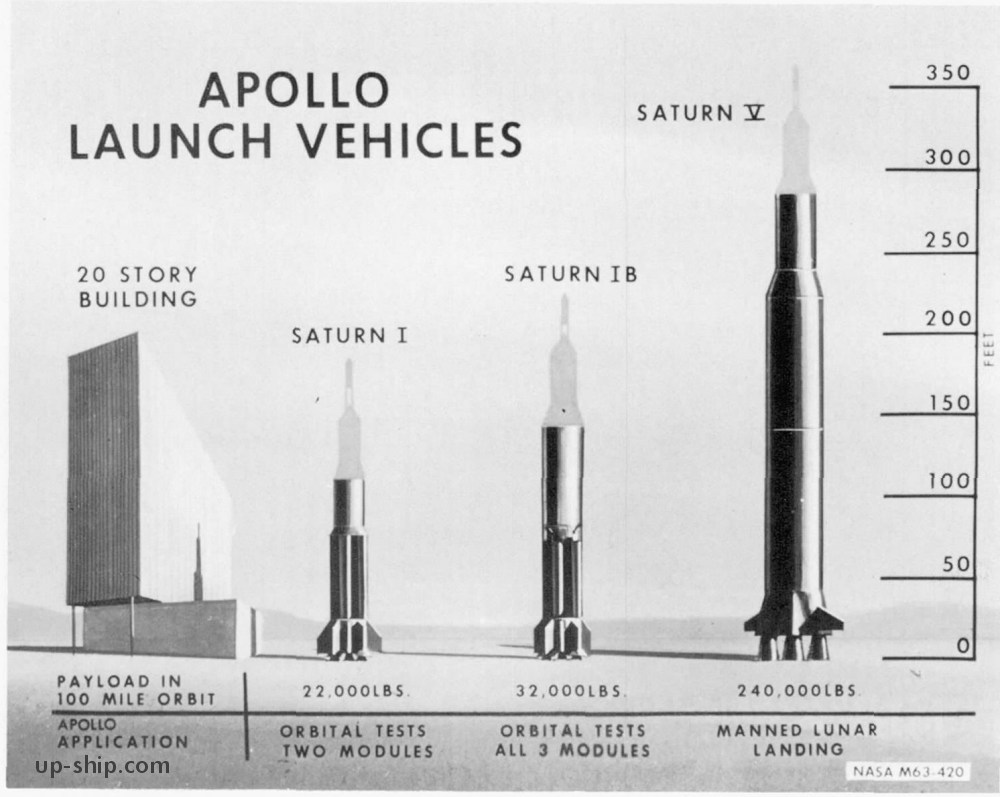

The Apollo Command, Service and Lunar modules, from 1963. The CSM is largely recognizable, but the lunar module is quite different from what actually got built. The ascent stage, for instance, still features very large – and very heavy – windows for the crew to look out of. This was due to the fact that the crew at this time were seated during landing, putting them well back from the windows.

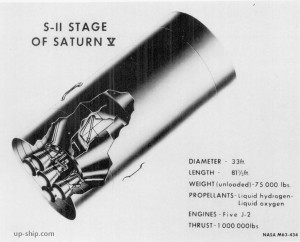

Found and photographed at the NASA-HQ historical archive was this painting depicting work being done upon an orbiting S-IVb stage. What’s happening is that small secondary payloads were to be installed in the Instrument Unit which ringed the top of the S-IVb stage below the conical main payload shroud, and they could be accessed by astronauts for use or retrieval. This is described in the Saturn V Payload Planner’s Guide (available HERE).

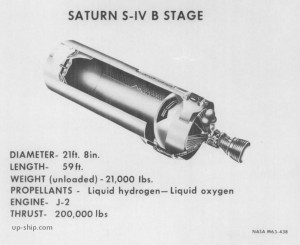

A 1966 Grumman concept for a long duration Lunar rover based on Lunar Module equipment, namely the crew compartment. Specifically, the cabin was from a Lunar Model derivative “lunar Shelter,” designed to land on the moon, but not to lift off again. By removing the rocket engine, propellant and other associated systems, a great deal of internal volume and payload mass would be made available. By mounting the cabin to a chassis with four wheels and 8 kilowatts of fuel cells, the MOLEM could provide a mobile shelter for two men for 14 days, permitting a total range of 250 nautical miles. Two 50 watt RTGS would be provided to power the MOLEM for up to 3 months after unmanned landing and the arrival of a crew. Other MOLEM drawings are HERE.