For $10 patrons on my Patreon campaign, a new message should appear there asking you to vote on what I’ll release in August (two documents and one large format diagram). For those who are $10 patrons, here’s a partial list anyway… if you see something there and you really want to make sure it becomes available, well, the obvious thing to do is sign on and vote!

———————-

Drawing: fairly detailed 3-view of Lunar Roving Vehicle (as actually flown to the moon)

Drawing: “Plans for Scale Model Construction of the Honest John Surface-to-Surface Missile” by McDonnell-Douglas, 1971 (does anyone know of more of these???)

Document: “Douglas Aircraft Company: An Overview,” 60+ page brochure showing existing and proposed jetliners, by McDonnell-Douglas, ca. 1980

Art: a vintage lithograph of the Lockheed L-2000 SST in flight, w/3 view on the back.

Document: “CT-39 International Sabreliner,” a Rockwell International booklet/brochure describing the multipurpose utility jet

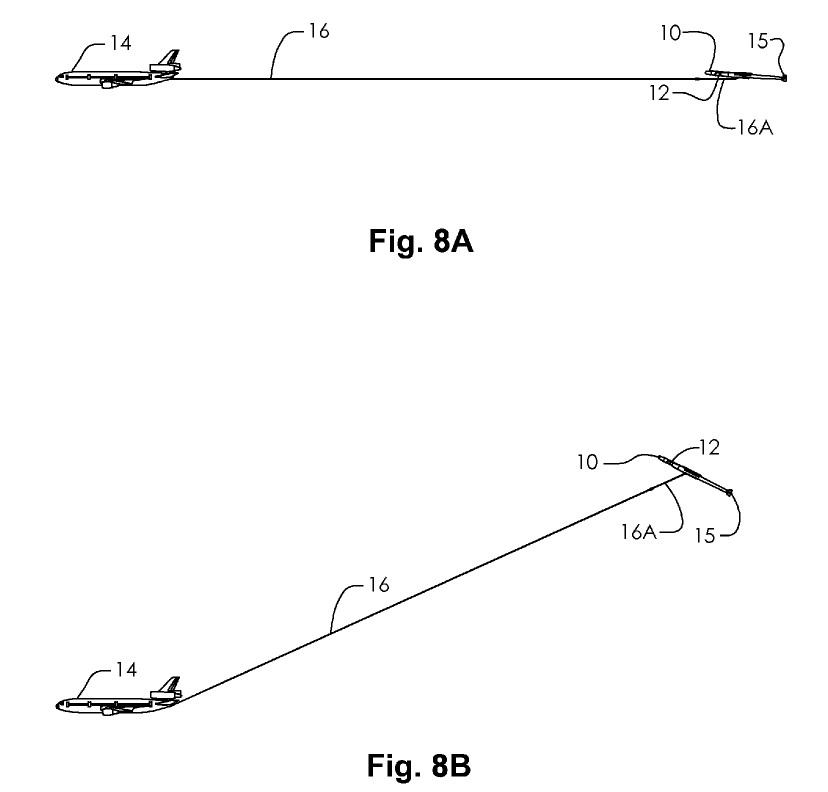

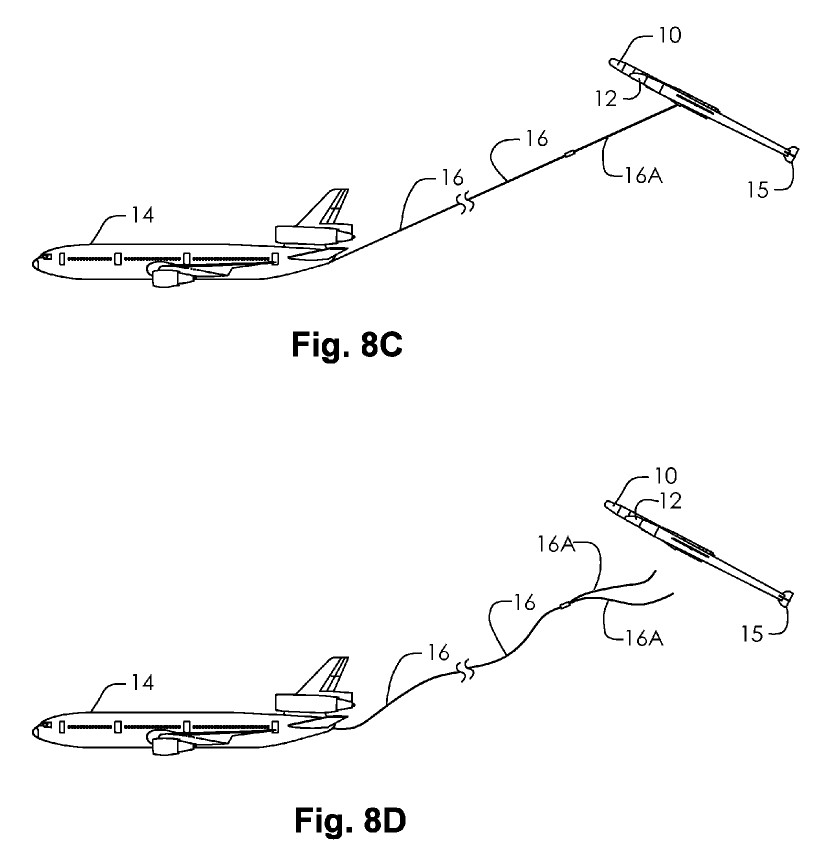

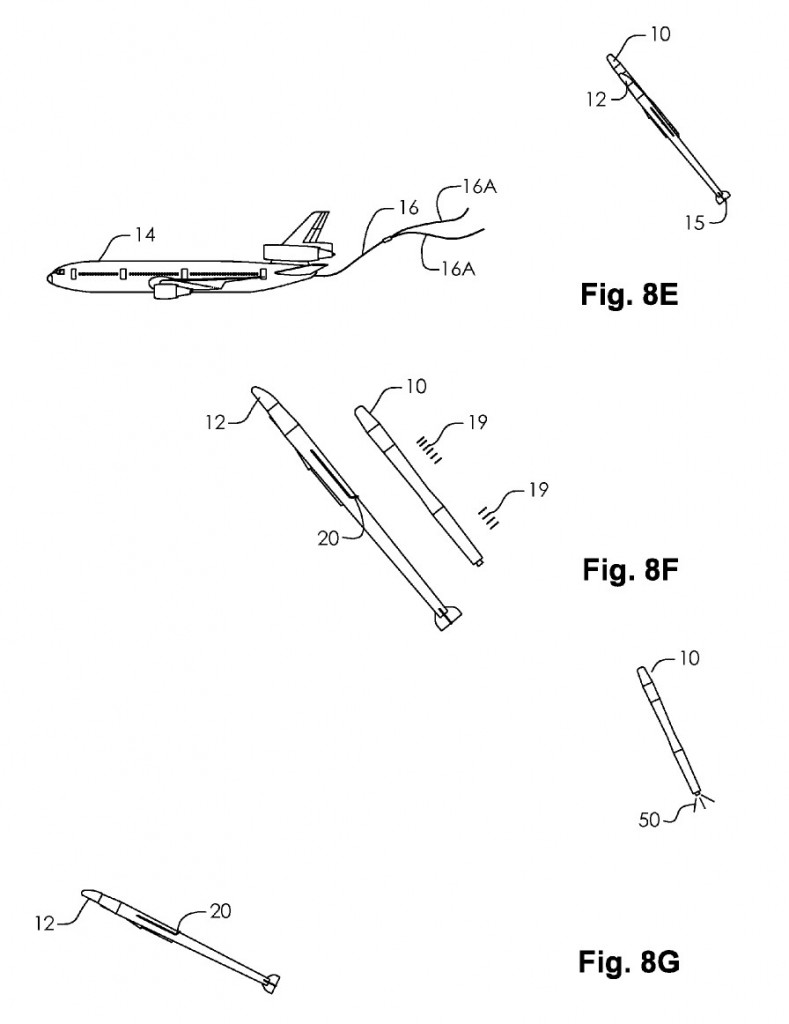

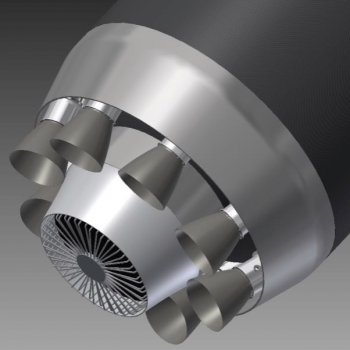

Document: “Air Force Expeditionary Catapult,” a truly massive billet of paper serving as a proposal from the All American Engineering Company for the System 300 Catapult, 1955. This was to be a turbojet-powered cable launching system for jet fighters which could be easily transported and set up in the field. (NOTE: this one counts as two reports, as it’s fairly gigantic)

Document: Aeroassisted Flight Experiment Nonadvocate Review, 1989, NASA

Document: Pocket Data for Rocket Engines, 1953, Bell

Document: SAM-D Air Defense Weapon System, 1973, US Army

Document: Pilots Handbook of Operation XLR11-RM-3 & XLR11-RM-5, liquid Rocket Engines, 1950, Reaction Motors

Art: X-15 lithograph (date unknown)

Document: The Centaur Program, 1961, Convair

Document: Orbiter Vehicle Structures, Rockwell

Document: An integrated Moonmobile-Spacesuit Concept, 1961, Aerojet

Document: The Intercontinental Stratoliner 707-320, 1955, Boeing

Document: Douglas DC-8 Design Study, 1953, Douglas

Document: Transport Weight Comparison Based on Lockheed 49-10, 1943, Lockheed

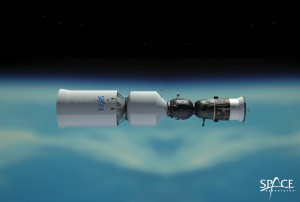

Document: ETR Launch Operations Plan for Cenaur on Shuttle, 1979, General Dynamics

Diagram: MD-11 wing diagram, six-feet long: McDonnel-Douglas, 1995

Document: A Lockheed presentation on the GL-224 Turbo-Jet VTOL Aircraft, 1958

Document: A Project RAND report on the GG-2 all-wing bomber, 1949

Document: A small Rockwell brochure on the “common core” concept for a fixed-wing subsonic B-1 variant, 1979 4) A presentation on the Douglas “Skybus,” 1944

Document: A NAA report on a turboprop-powered F-82E for ground attack, 1949

Document: A Curtis report on the twin engined F-87C, 1948

Document: A Vertol report on VTOL transport aircraft, showing several very different configurations, 1956

Document: A Lockheed presentation to the AIAA on the history of the Fleet Ballistic Missile, 1978

Document: A collection of Manned Spacecraft Center Space Shuttle orbiter concepts, 1972

Document: A Convair collection of design drawings of an Assault Seaplane, 1948 (NOTE: this one counts as two reports, as it’s fairly gigantic)

Document: A Vought report on the Regulus II missile with detailed diagrams, 1955