The OPEC oil embargo of the west of 1973-74 and subsequent skyrocketing of petroleum prices made sure that the American SST program, cancelled by Congress in 1971, stayed cancelled. As Concord subsequently showed, an SST in an era of expensive aviation fuel would be an economic disaster.

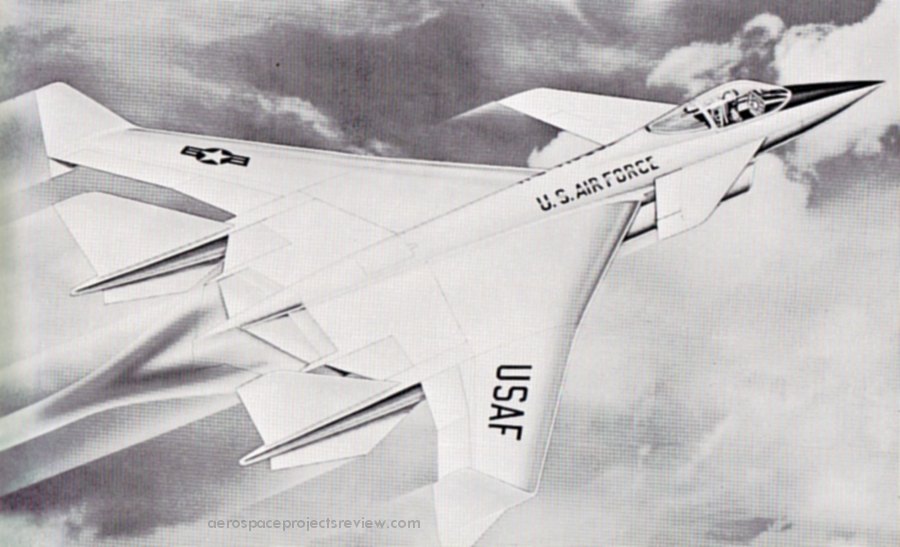

In the late 1970’s there was a flirtation in the American aviation industry with liquid hydrogen as an alternate fuel for jetliners. LH2 would pose a number of issues, not least of which being the very low density of the stuff; relatively gigantic heavily insulated fuel tanks would be needed. For subsonic jetliner designs, these tanks often took the shape of extremely large fuel tanks on the wings, nearly the size of the aircraft fuselage. This was not much of an option for supersonic transports due to the increased drag. Nevertheless, liquid hydrogen fueled supersonic transports were designed. One such is shown below, a late 1970’s Lockheed design. The liquid hydrogen tanks occupy much of the forward and aft fuselage volume; the passengers are stuck in a relatively short segment in the middle of the double-deck fuselage. There would be no direct connection between the passenger compartment and the cockpit… so at the very least, the likelihood of a hijacking – another feature of air travel in the late 1970’s – would be greatly reduced.

By the 1980s, efforts to wean the west off OPEC petroleum were bearing fruit (or at least looking promising); as a result, the price of oil plummeted. And with cheap oil the imperative to design hydrogen-fueled aircraft largely vanished.