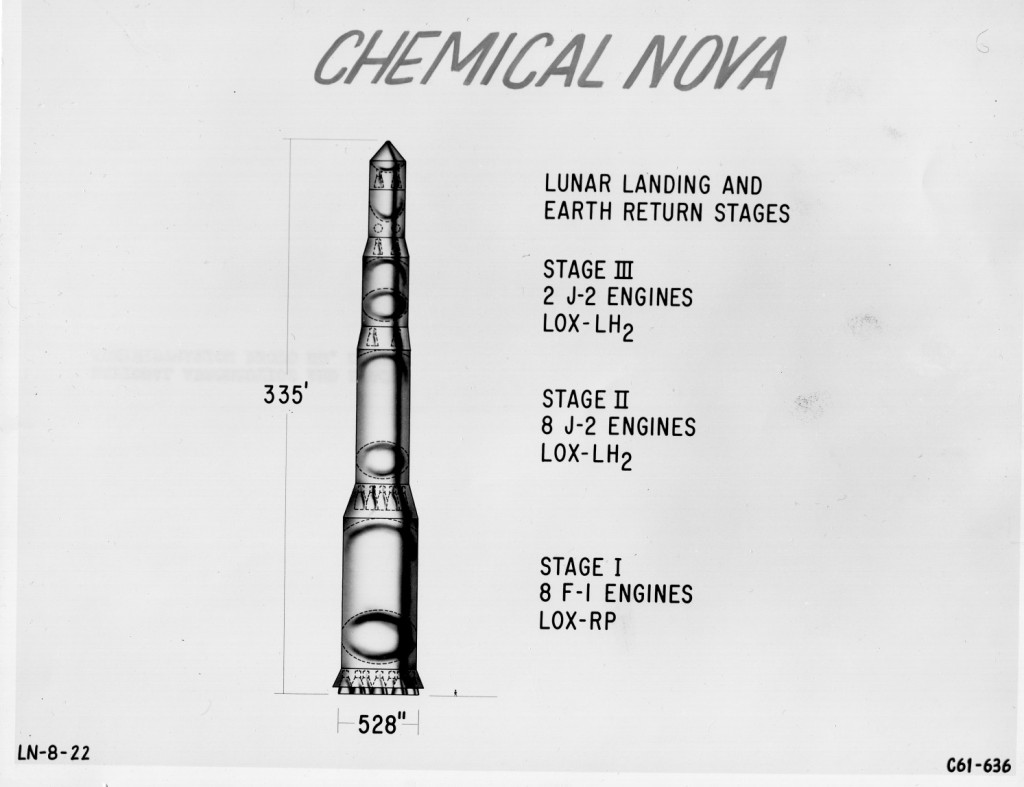

A piece of NASA presentation artwork from 1961 showing a basic design for an all-chemical-rocket design for a Nova launch vehicle. This would have been somewhat more powerful than the as-yet undesigned Saturn V; and it would have needed to be in order to carry of its mission. The Lunar Orbit Rendezvous design had not yet been chosen, and consequently the Apollo capsule and the service module both would have been landed directly on the lunar surface.

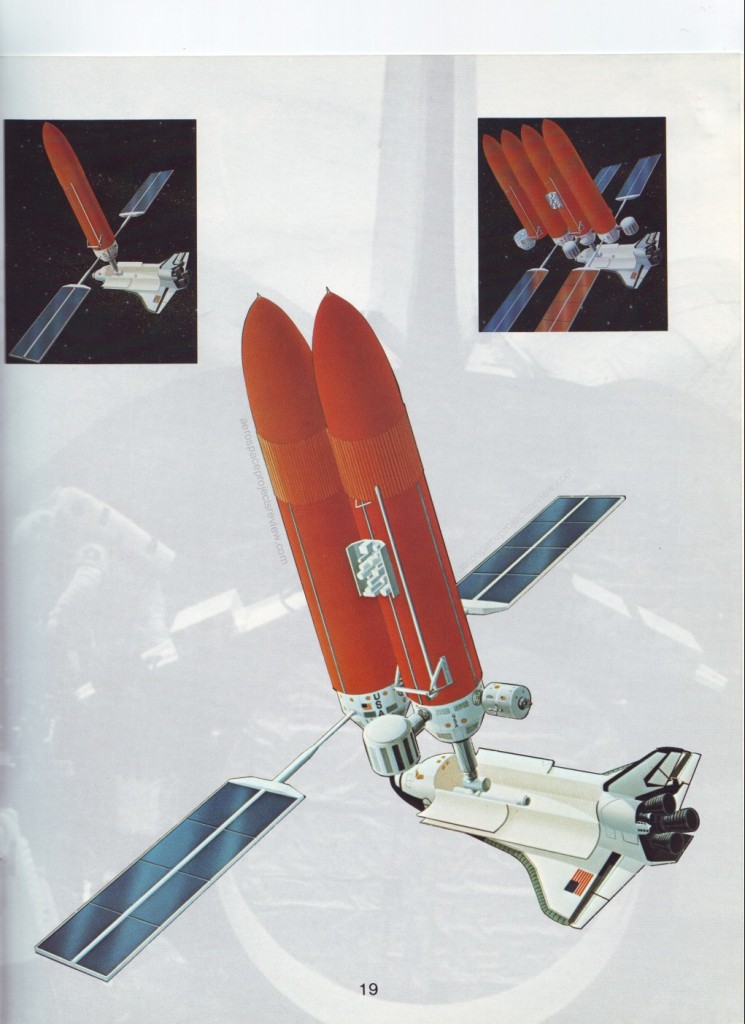

Another brochure illustration showing the ACC in use supporting the development of external tank based space stations. This time, SpaceLab components are shown attached to the outside of ET space stations. This would have meant that the ETs would have had to have had fittings welded onto them, either on the ground before launch or while in orbit, or otherwise holes drilled or punched into them on orbit for bolts or some other mechanical fasteners. Poking holes in the tanks would of course ruin them as pressure vessels; in this case they’d be good only as structural attachments.

Another issue would be the insulating foam. Over time, environmental conditions (extremes of hold and cold over 90-minutes orbits) would cause the foam to degrade and flake off, surrounding the station with a comet-tail of debris.

More on the ACC – the complete 22-page brochure – is available HERE.

The Martin Marietta Aft Cargo Carrier would have allowed the Space Shuttle to transport payloads of larger diameter by carrying them on the aft end of the External Tank, rather than in the Orbiters cargo bay. This would of course have necessitated that the ET be carried all the way to orbit; consequently, the ET would be on-hand and available for use.The illustration below shows how a fairly small number of Shuttle launches could have resulted in a truly vast space station.

More on the ACC – the complete 22-page brochure – is available HERE.

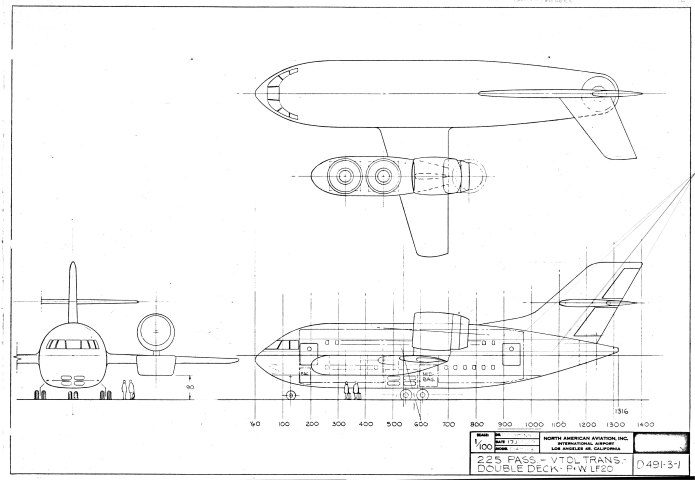

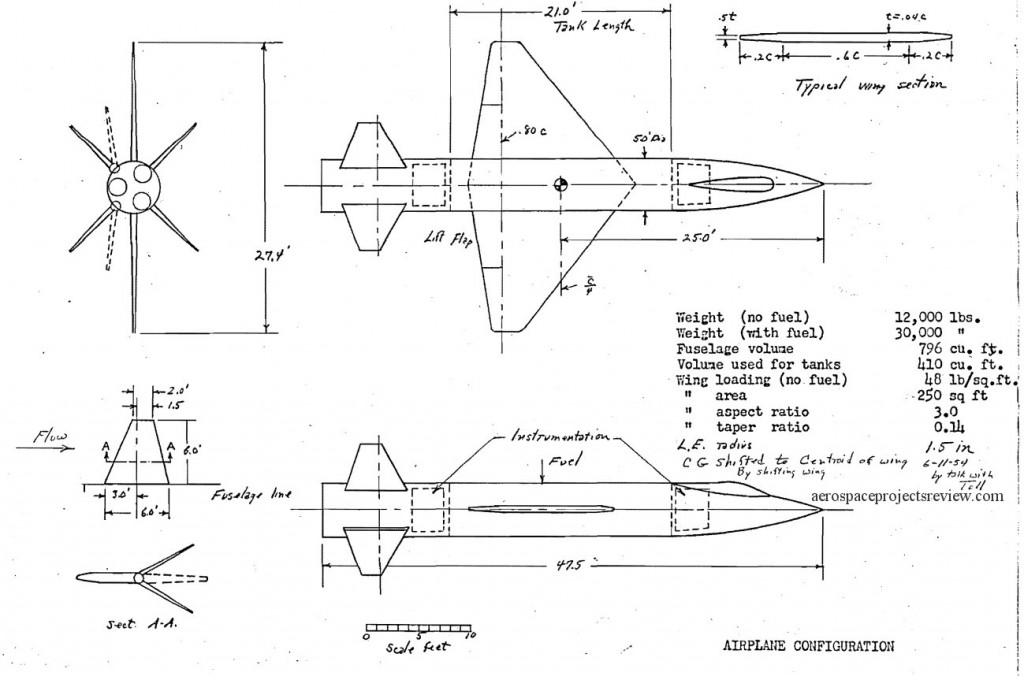

Standard Aircraft Characteristics sheets describing the Boeing XB-52 as of December 1949. This was not the B-52 as it was actually built… a number of design changes were yet to come. Most notable is that the wing is much closer to the nose. The cockpit in fact extends aft beyond the leading edge of the wing root.

SAC sheets used to be produced in large numbers to describe in concise form not only the aircraft the USAF was flying, but aircraft it was hoping to fly. These sheets would be produced by the USAF or by the contractors; contractors would often produce SACs describing conceptual or preliminary designs. There does not seem to have been a central clearinghouse for them… they were produced and distributed with no readily apparent rhyme or reason.

The quality is terrible, but apart from photos of a display model, this is the only illustration have of Northrop’s design for SLOMAR (Space LOgistics Maintenance And Rescue), a USAF program circa 1961 to study the sort of spacecraft that would be needed for crew and cargo transport to the space stations that everyone knew the USAF would have in some abundance by the end of the decade. The Northrop design is virtually identical in configuration to the Boeing Dyna Soar, though apparently a bit bigger.

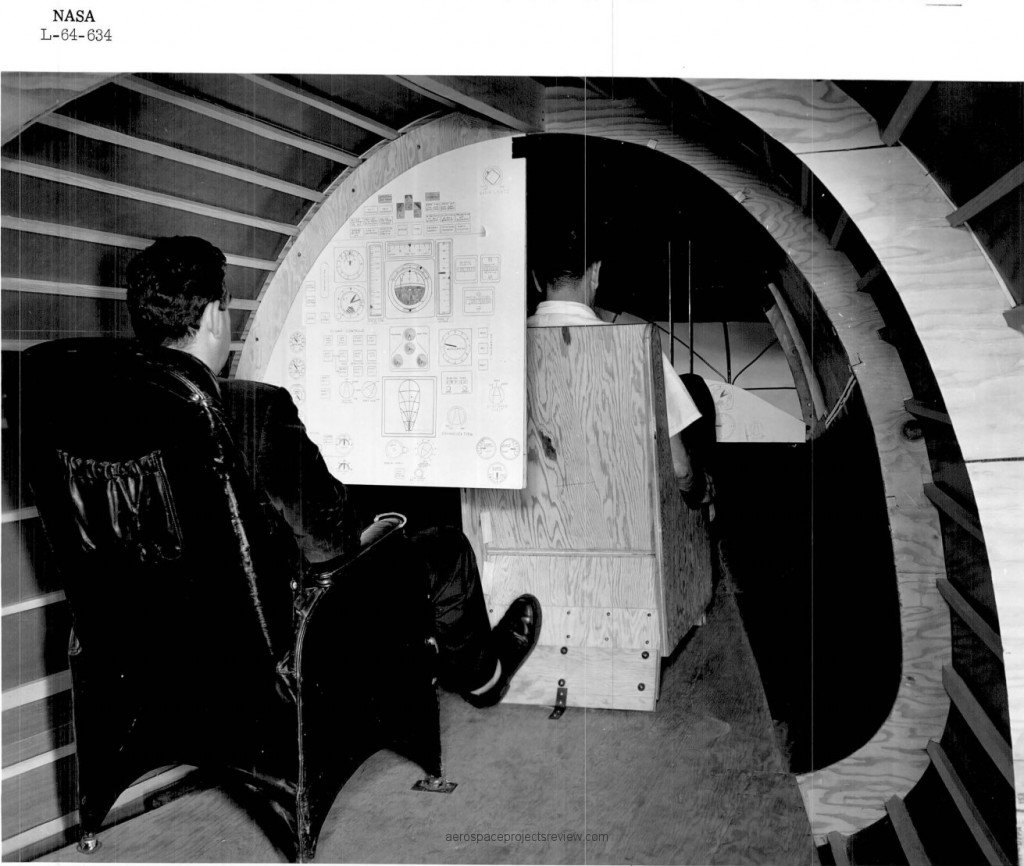

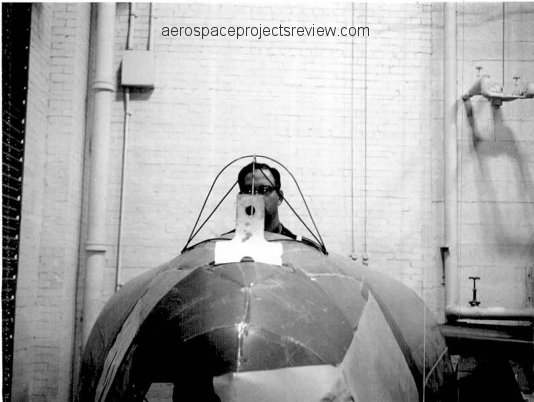

This one, based on the same crude mockup, moved the pilot lower. It is much more like the HL-10 as actually built, with no disruptions to the basic lifting body mold line. It does have a quite different window arrangement, however.

Curiously, it seems that seating for more crew than just the pilot was considered. This indicates that this planning wasn’t just for a purely research vehicle, but an orbital vehicle intended to transport a crew.

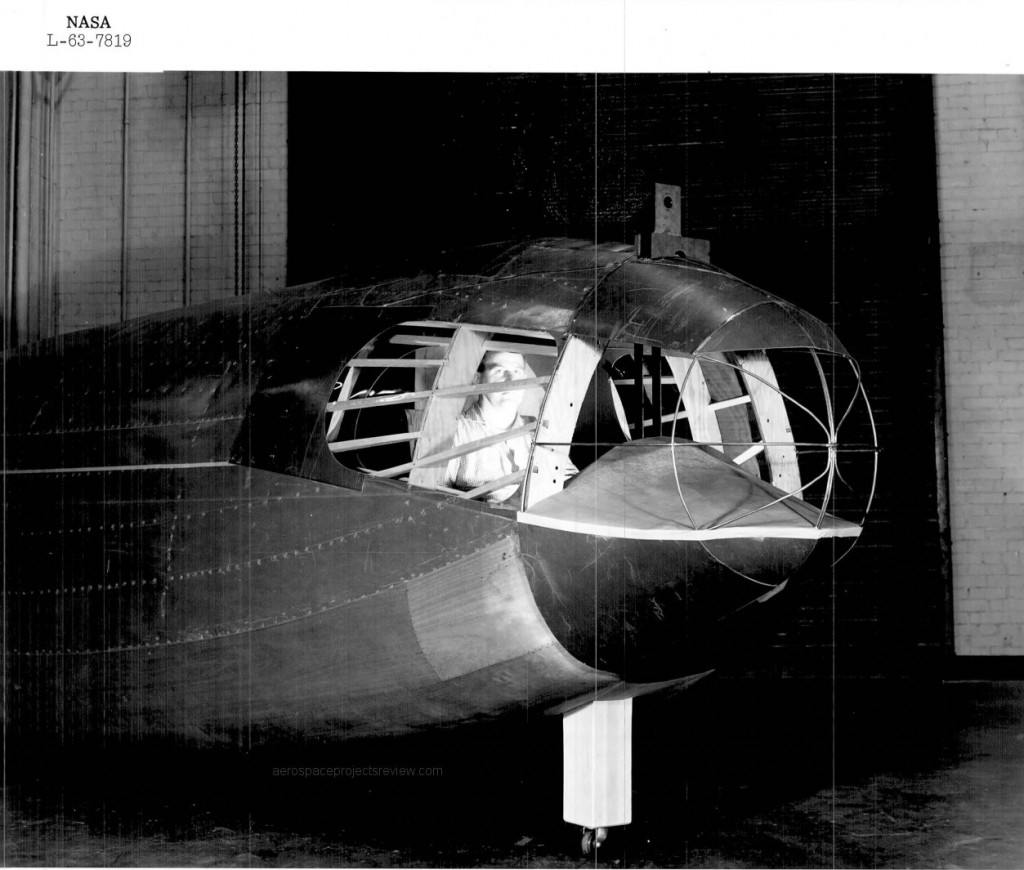

From photos circa 1963-1964 show a full-scale NASA-Langley mockup of the forward nose section of the HL-10 lifting body shape. Incorporated into this was a framework showing a potential canopy configuration. This would clearly have been for a low-speed (non-orbital) test version, much like the HL-10 that was actually built.