Sep 272018

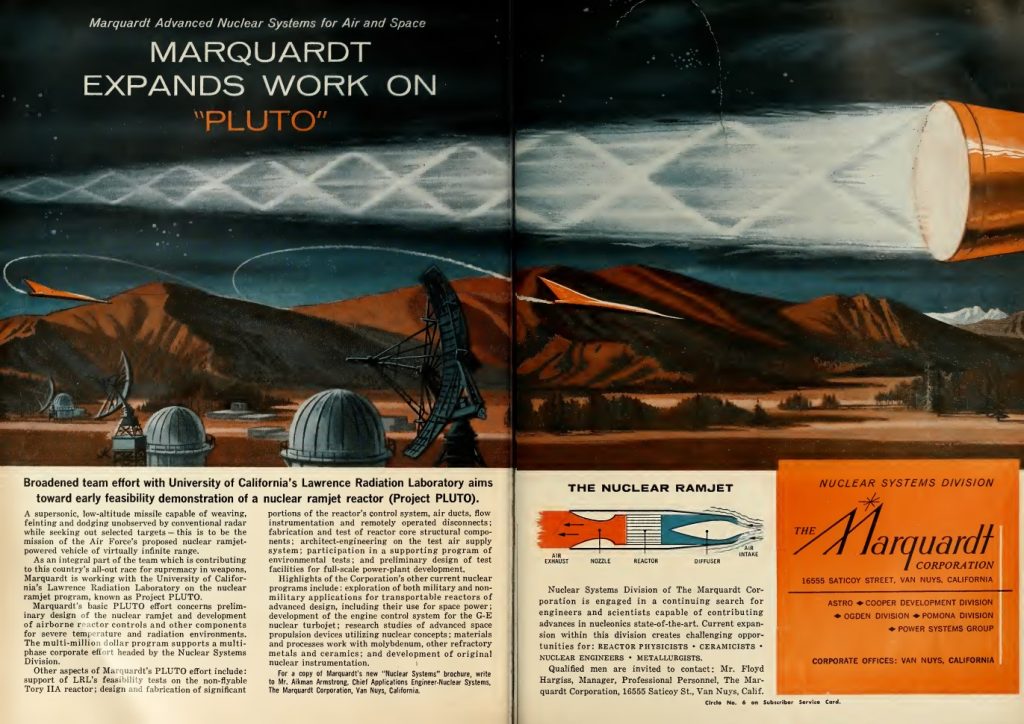

An advertisement from 1960, illustrating Marquardts work on the Project Pluto nuclear ramjet:

If you want more on Project Pluto – and who wouldn’t, as the idea of a locomotive-sized cruise missile flying at virtually unlimited range at tree to level and at a blistering Mach 3+ is fascinating – check out Aerospace Projects Review issue V2N1.

It’s amazing that Project Pluto progressed as far as it did before it was cancelled. It would have caused terrible damage to anything it passed over through a combination of supersonic shock waves and radiation, so where do you test it? To fully validate the auto-pilot they would have had to fly it repeatedly over the kind of European landscapes that it would pass through in any attack on Soviet targets, which are also the kind of landscapes that tend to be widely inhabited.

What do you do with a malfunctioning test article that is about to exit the range? Can you trigger a self-destruct without scattering radioactive fallout all over the area? How can you conduct maintenance or testing on a missile that is too radioactive to approach? It should have been obvious at a very early stage of design that the whole concept was totally impractical.

Perhaps the real historical significance of Project Pluto is as a demonstration of the attitudes in that period of the Cold War, in which both sides were so desperate to gain any possible advantage that they were willing to throw money at projects that now seem ludicrous.

Pluto was intended to be tested over the Pacific, running laps until it was to be intentionally driven into the ocean above the Marianas Trench. As for the terrain mapped radar, testing would be possible using other, less terrifying, aircraft and missiles.

A Pluto missile would not be dangerously radioactive until the reactor was fired up for the first time. And at that point there’d be no maintenance, any more than you’d maintain a Polaris missile in flight.